South America: "Green" Destruction in the Amazon Rainforest

International Secretariat World Rainforest Movement (WRM)

For decades, Latin America and the Caribbean have suffered the world’s highest rate of tropical deforestation, higher than Africa or Asia. From 2001-2013, on average about 4.2 million hectares were destroyed every year in the region, compared to 2.3 and 1.8 million hectares per year in Asia and Africa, respectively. In the 2014-2018 period, this average rate in Latin America reached 5.5 million hectares per year.

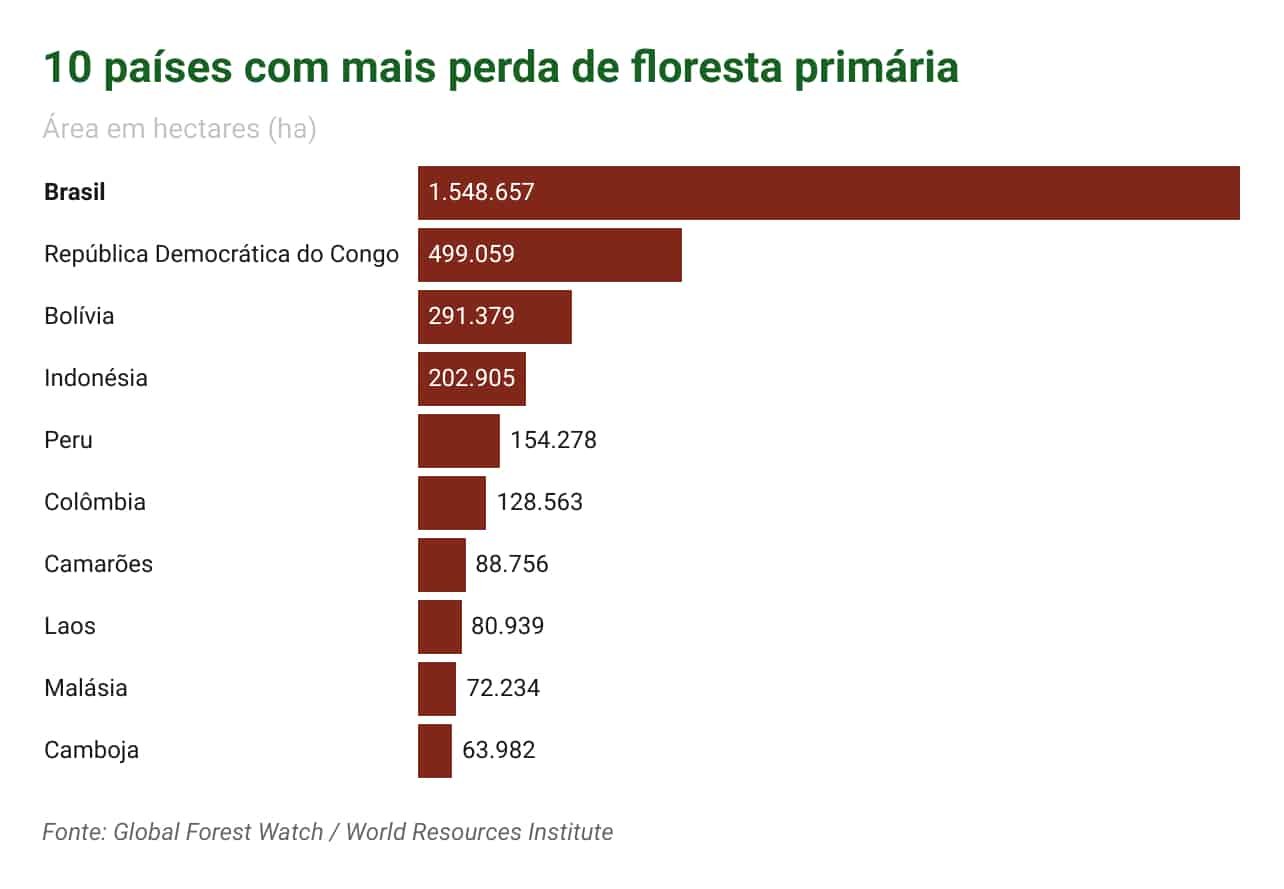

Much of this destruction in Latin America is concentrated in the Amazon region. In 2021, among the 10 countries with the highest loss of primary tropical forests in the world, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia rank first, third, fifth and sixth, respectively. In these four countries alone, 2.12 million hectares of forest were devastated that year.

To understand the process of deforestation we must go beyond its most visible causes, such as timber extraction and the advance of agribusiness and mining, to perceive, most of all, its underlying causes. These tend to be hidden, less discussed and misunderstood, and are closely linked to various forms of oppression under the capitalist-racist-patriarchal system, as well as to the region’s colonial legacy. In addition, more recently, we need to understand how projects touted as “solutions” to the climate crisis have themselves become new underlying causes of deforestation.

The first and only comprehensive analysis of these causes on a global scale was carried out in 1999[1], coordinated by the United Nations, with the significant participation of civil society organizations in the main forest countries.

What is most striking in rereading the causes identified in 1999 is that most of them are still extremely current[2]:

- Large "development" or infrastructure projects such as dams, roads and mining and oil-extraction schemes are perpetuated by corporate-state alliances;

- Agribusiness, arguably more destructive today than in 1999, continues to advance, as part of a larger process of logging, forest fires, speculation, and land grabbing;

- Investment patterns, indebtedness, macroeconomic policies, global commodity flows, and trade relations continue to be central to deforestation processes worldwide;

- Laws still allow public land to be granted, for example, to timber, mining, or tree plantation large companies;

- Many "nature conservation" projects continue to harass and dispossess forest peoples to set up official protected areas;

- Militarized methods of centralizing control over forests are still being employed by states, global corporations, NGOs, or even by all three.

- The territorial rights of indigenous peoples and traditional communities are still not adequately recognized, and discrimination persists. In recent years, the criminalization of communities and peoples has increased, while destructive activities are "decriminalized", and at times explicitly encouraged;

- Attacks on the livelihoods and struggles of forest defenders continue to undermine forest protection.

Notes

The final 1999 report was entitled “Addressing the Underlying Causes of Deforestation and Forest Degradation – Case Studies, Analysis and Policy Recommendations”.

Today’s old causes of deforestation

Deforestation in Latin America and the Caribbean is bigger not only because the Amazon is the largest tropical forest in the world, but also because of the scale and speed of growing agribusiness, mining, fossil fuel extraction and infrastructure activities.

With Venezuela’s economic crisis, for example, predatory extractivism has taken hold, based not so much on oil as on other forms of mining. The main project is the Orinoco Mining Arc, covering 12% of the entire country, partially in Venezuela’s Amazon region, with private and international capital. In 2016, the government created a Special Economic Zone – a geographical area with special laws that drastically relax environmental standards and social rights, among other problems. At the same time, the government has made deals with participating companies, whose details were never publicly disclosed. The army was also given special powers to ensure that mining will go on and resistance will be suppressed[3].

Another example is infrastructure, built under the guise of promoting South American “development” and “integration”. However, these highways, railroads, and waterways, as well as ports, airports, and hydroelectric dams, serve mainly to enable the growing volume of raw materials and products from extractive activities. They do not meet the needs of local populations, and often leave nothing but devastating impacts.

The main plan for South America is the Initiative for the Integration of South American Regional Infrastructure, IIRSA. The IIRSA Plan was launched in the year 2000 by 12 South American governments, envisaging more than 500 projects. Gradually, infrastructure investments have become the newest form of financial capital expansion, with a potential for huge profits, mainly through public-private partnerships advantageous for the private sector, while national governments bear the risks[4]. Nowadays, we hear about “extreme infrastructure” projects. These are mega-corridors connecting places where extraction is cheapest to manufacturing and consumption centers on an ever-increasing scale and speed[5].

One example is the construction of a stretch of the “inter-oceanic highway” between the city of Cruzeiro do Sul in Brazil and Pucallpa in Peru, which would link northwestern Brazil to southwestern Peru. This construction began more than 20 years ago. In an open letter, indigenous peoples from both countries oppose the project, denouncing that “the construction of the highway is part of a predatory development model that includes mining, timber, oil and gas exploitation. Situated in the region with the world’s largest surface freshwater basin, it has undemarcated indigenous lands and is home to peoples in voluntary isolation, who continue to be ignored and denied.”[6]

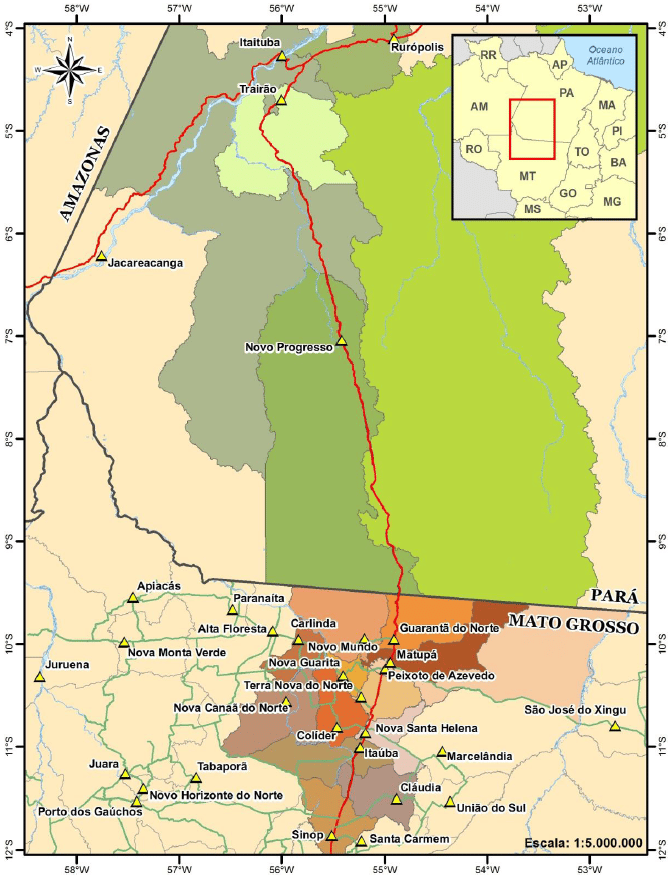

The already harmful impacts of such highways are compounded by railroad projects in the Brazilian Amazon. The so-called “Ferrogrão” railway, for example, to connect northern Mato Grosso state to the port of Miritituba on the Tapajós River in Pará state, will pass through Conservation Units and Indigenous Lands, and tends to further aggravate the impacts of highway BR-163, which enters the Amazon from the Center-West region, the country’s largest grain producer[7]. Historically, projects like these have driven even more deforestation, with devastating impacts on forest peoples.

Notes

Emilio Teran Mantovani: Crisis and oil depletion in Venezuela: Mega-mining and new frontiers of extraction, 2017, and Emilio Teran Mantovani: Predatory mining in Venezuela: The Orinoco Mining Arc, enclave economies and the National Mining Plan, 2021.

Nick Hildyard, Accelerating deforestation: Financialization as a driver of infrastructure projects, 2014.

Nick Hildyard, Ever More Extreme Infrastructure, 2019.

Final Document from the Brazil-Peru Binational Seminar, 2022. “Amazônia: Sociobiodiversidade, resistência ao modelo desenvolvimentista predatório (in Portuguese).

“Ferrogrão e o novo ciclo de exploração da Amazônia”, 2021 (in Portuguese).

The “greening” of destruction: new underlying causes of deforestation

The fact that the underlying causes of deforestation identified in 1999 are still current does not mean that nothing has changed. Most of the so-called “solutions” put forward to address deforestation since then by governments, banks, big preservationist NGOs[8], and others have become new underlying causes.

The main one is the REDD mechanism, which stands for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. REDD emerged from UN climate conferences in 2005 as a promise to reduce and fight deforestation quickly, simply, and cheaply, and thereby reduce both carbon emissions into the atmosphere and the impact of climate change. The argument was that it would be more advantageous to “Keep Forests Standing” than to cut them down.

In tropical forests, to approve a REDD project, a company or NGO chooses an area of supposedly threatened forest and makes a projection of how much of it would be deforested within 30 to 50 years. Then a hypothetical calculation projects how many hectares would be conserved if their REDD project were implemented there and, next step, the volume of carbon emissions that would be avoided. Those calculations are then used to issue tradeable carbon credits, all certified by consulting companies.

These credits can be purchased, for example, by oil extraction, aviation, food commodity, or mining corporations, most of them in the global North. They “offset” the pollution they generate by claiming to conserve faraway forests. By doing so, they “buy” the right to go on polluting the atmosphere with an amount of carbon supposedly equivalent to what has been “saved” in the forest area whose destruction has been “avoided”. “Offset”, therefore, is a buzzword for the REDD mechanism[9].

What’s more, REDD projects are often set up in forest-dependent communities’ territories, which need not be officially demarcated. As designated culprits for deforestation, they are now prevented from using their own spaces to carry out activities that are fundamental to their livelihoods. REDD systems thus reinforce the mistaken assumption that there is no way for people and forests to coexist – as if communities’ ways of life are in any way comparable to the scale of destruction wrought by agribusiness, which is clearly antagonistic to forest conservation. Thus, REDD causes problems for communities at both ends: in the forests where the projects are located[10], but also in communities living around companies in the global north as the REDD schemes allow them to continue to pollute.

Since the REDD mechanism was launched nearly two decades ago, deforestation has not been reduced, quite the contrary. Its more than 300 projects[11] around the world have never prioritized locations where deforestation is greatest. Agribusiness activities, mining, monocrop tree plantations and others have always been more profitable than keeping forests intact, thus revealing the true intention behind projects like REDD: perpetuating the right to pollute. They contribute to worsening the climate crisis instead of mitigating it.

Notes

When we talk about “preservation” or “preservationist” entities, we refer to their idea that the survival of forests depends on the creation of “protected areas” or “national parks”, preferably with no human communities inside them, based on the opinion that humans destroy nature. In contrast, “conservationism” understands that the presence and participation of the communities who depend on the forests is fundamental to protect the forests. Many studies around the world show that forests exist thanks to the presence of human communities who have taken care of the forest, which they consider their “home,” since with no forest they have no livelihood.

To understand why REDD does nothing to reduce the impact of climate change, see: “10 things communities should know about REDD – Re-launched with a new introduction”.

WRM, “REDD: A Collection of Conflicts, Contradictions and Lies”, 3 December 2014.

A study on the municipality of Portel, Pará, Brazil, recently published by the World Rainforest Movement (WRM)[12], shows that the location of four REDD projects, occupying a total area equivalent to almost 20 per cent of Switzerland’s surface area, is not in the municipality’s areas with the greatest imminence of deforestation – which are the areas closest to the Transamazonian highway, where there has been the highest concentration of forest fires[13].

Portel’s REDD projects, instead, are located inside the territories of riverside dwellers communities (“ribeirinhas”). There, the proponents of the projects have helped residents file their Rural Environmental Registry (CAR, Cadastro Ambiental Rural) papers, for areas of about 100 hectares, alleging in bad faith that the registration is a land title. Unknowingly, by accepting the CAR, the riverside dweller families end up agreeing to the implicit condition that they must limit their livelihood activities to that registered area. It means that they have no permission to enter the rest of the REDD projects’ area, thus excluding their access to a larger territory where they have always carried out traditional activities such as burning small areas to grow crops, plant fruit trees, and collect food and other forest products.

One of the companies that has purchased “rights to pollute” from the Portel project is the French airline Air France. The company claims that all its domestic flights are now “’carbon neutral”, supposedly “offset’” with credits bought from the project in Portel and others in the Amazon. World aviation accounts for 3.5% of human impacts on global warming[14]. In addition to Air France, the Portel projects have sold “pollution credits” to more than 400 other companies, including corporations such as Samsung, Repsol, Amazon, Toshiba, Delta Airlines, Boeing, Kingston, and even the Liverpool Football Club.

Notes

WRM. “Neocolonialism in the Amazon: REDD Projects in Portel, Brazil”, 9 November 2022.

REDD+ IN AMAZON: Monitoring of Wildfires and Burnt Areas.

The “greening” of destruction: new underlying causes of deforestation

At this time, 99 REDD projects have been certified or are in the process of certification[15] in the four countries with the highest deforestation rates in the Amazon region (Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia). In addition, there is an unknown number of other uncertified REDD initiatives.

There are also several programs proposed by national governments in the Amazon region. In Colombia, for example, a 2017 decree allows companies to achieve “carbon neutrality” by purchasing “offsets” through such means as REDD projects. They are thereby exempted from “polluter pays” taxes, levied on corporate “carbon” emissions under an earlier 2016 law with incentives for companies to reduce their pollution. By 2021, there were records of 75 such REDD projects in the country.[16]

There are also state government REDD programs, such as in the states of Acre and Mato Grosso in Brazil, funded by the governments of Germany, Norway, and the United Kingdom. Payments in this case do not come from the sale of credits on the carbon market, but are based on purported “results”, as state governments are “rewarded” for having reduced their deforestation rates over a certain period in the past, as agreed by the parties.

Both parties also agree on a deforestation rate they find acceptable at present, and payments in subsequent years occur if deforestation does not exceed that rate. This can lead to a contradictory situation in which these governments receive payments even when deforestation is on the rise, as has been the case in Mato Grosso. Furthermore, although this kind of REDD program is not funded by the carbon market, one of its main objectives is to prepare these states to enter that market as soon as possible.

Let us not forget either that the largest recent reduction in deforestation in Brazil took place in the period (2004 to 2009) in which there were practically no REDD projects in Brazil, and that the reduction was largely due to effective public policies.

The New REDD: Nature-Based Solutions (NBS)

REDD’s shortcomings might suggest that the idea be dropped, but that has not been the case. For some, REDD has not been a failure. Major preservationist NGOs, carbon market companies, consultants who design and validate projects, national and state governments, certifiers, and others have collectively pocketed billions of dollars from REDD projects over the past 15 years. Nor has REDD been a failure for big corporations like the oil companies, which have been able to expand their polluting activities by claiming to “offset” their emissions.

They did, however, decide to change the name. REDD is now coming to be known as Nature-Based Solutions (NBS)[17]. NBS were launched several years ago by the IUCN[18], and re-launched in 2019 at the UN climate conference based on a study by the NGO TNC (The Nature Conservancy). That study was predicated on highly dubious assumptions: that by 2030 NBS would be able to deliver about a third of the emissions reductions needed to minimally control climate chaos. This means that a growing number of REDD-type offset projects will be tabled under this new name. NBS initiatives also became even more hazardous to forest peoples because they are linked into another proposal, the so-called “30×30” plan, which aims to conserve 30% of the world’s natural areas by 2030.+

The mantra of the moment for all sectors of global industry is to achieve a “carbon-neutral” level of emissions. Instead of drastically reducing their pollution and emissions, which would compromise profits, they prefer to “offset” their pollution with NBS, in particular by “protecting forests”, which does nothing to help save the climate, as we have explained.

This has led to a veritable forest-land rush into the Amazon by companies and NGOs. Many communities are being harassed to sign contracts with “carbon” companies anxious to sell pollution credits to overseas industries, and increasingly also to domestic companies[19]. This new trend has not yet spawned explicit NBS projects in the Amazon. But when it does, they are expected to follow the logic of the REDD mechanism and to be even larger[20].

Since NBS can also be applied to agriculture, Brazilian agribusiness has become one of the world’s most prominent players, for example expanding its eucalyptus plantations and so-called “low carbon agriculture”[21] initiatives. Such plans also mean including new additives in animal feed and introducing agroforestry and soil management practices. All this is an aberration, when we consider their plans for mega-expansion, using fires and deforestation. Not to mention the consumption of petroleum-based products throughout the entire chain, including chemical fertilizers and pesticides, which is why the agribusiness food commodities chain is already responsible for up to 37% of all global greenhouse emissions[22].

The "low carbon" or "green" economy

Big finance and industrial capitalists, however, are thinking about more than just painting themselves “green” with “carbon-neutral” projects. They claim to have set in motion a transition for society’s energy base. Yet rather than moving towards a more climatically and socially just economy, they actually expect their “low-carbon” or “green” economy to maintain and strengthen their own hegemony and power. While mechanisms like REDD and NBS ensure long-lasting profits in an economy dependent on fossil fuels, they also know that at some point they must diversify their energy sources, since oil alone will not be enough. In addition, there are enormous pressures from civil society, investors, and consumers for a “greener” world.

It is a mistake to think that this new energy matrix, based on wind energy, mega hydroelectric plants, biomass, solar, and other sources, will reduce deforestation and/or extractive activities. On the contrary, these projects will also demand large amounts of land. The symbol of the “low-carbon economy” is the electric car, which, in addition to the usual metals and minerals – such as iron and aluminum – depends on several new minerals and metals whose extraction will imply even more destruction and deforestation.

Ecuador is an example of how the new “low-carbon economy” already impacts the forest and its people. Recent years have brought a rush into the forest to extract balsa trees, an ideal wood for China’s growing wind turbine industry, making Ecuador the world’s largest exporter of this material. Ironically, as China announces its goals of “carbon neutrality” through more wind farms, the destruction of forests to obtain balsa trees is escalating in Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru, to say nothing of other impacts: problems such as rivers polluted by mobile sawmills in the communities; forests thrown off balance by uncontrolled extraction; and social impacts such as labor exploitation, conflicts, and divisions in the communities[23].

Final considerations

Many of these top-down “solutions” to fight deforestation and the climate crisis are dressed up with promises and seductive short- and long-term benefits, often delivered by NGOs claiming to be forest- and community-friendly. Yet their “low-carbon economy” rhetoric can actually promote the interests of corporations that are destroying forests on a large scale.

These are perverse proposals and mechanisms because their central goal is to throw a lifeline to polluting industries – and their profits – while destabilizing the global climate in a short period of time. NBS, even more than REDD, will soon invade community territories, with the same old destructive activities, plus brand new “green” onslaughts.

This scenario underlines the importance of strengthening resistance in territories affected by the imposition of such destructive and/or “green” projects, and of networking, unity, and mutual solidarity among threatened communities. All the more so because deforestation and “green” projects depend on and actually enable each other. They are both part of a single, nefarious logic that must be exposed and opposed

Notes

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), composed of government and civil society organizations.

Since the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement, not only the countries traditionally responsible for large carbon emissions – Europe, North America, Japan, Australia – must set their carbon emission reduction targets. Now all countries that signed the Agreement, including South American countries, have this obligation.

The Biofílica company in Brazil, for example, which is behind several REDD projects in the Brazilian Amazon, such as the REDD project proposed for the Tapajós-Arapiuns RESEX in 2015, but rejected by the Reserve’s residents, was acquired by the AmbiPar Group in 2021. AmbiPar announced that “the expansion plan for the coming months foresees massive investments in the development of Nature-Based-Solutions (NBS) carbon projects and programs” (in Portuguese).

Acción Ecológica, “The green paradoxes of an Amazonian country”, 2021.

International Secretariat of the World Rainforest Movement (WRM)