A President and a Parliament serving land grabbers through lawmaking and deregulation

By Joice Bonfim and Larissa Packer

The twists and turns in the history of Brazil’s land legislation regarding public lands and its interface with environmental issues reveal deep-rooted interests and issues at play in the private – and illegal – appropriation of land and of nature. It is no wonder that the legal regime on land ownership in Brazil parallels – and legitimizes – the progressive exclusion of all others (non-owners) from access to land and livelihoods at various moments in the country’s history. Since European colonization, marked by the genocide and enslavement of black and indigenous peoples – who were not subjects of law capable of holding property rights – and also in more recent times, marked by an offensive to privatize and commodify public lands and nature, the legal regime governing private property has had its meaning and scope redefined to help dispossess peoples and capture the commons, to the exclusion of present and future generations.

The timeline below shows that the historical process of land occupation in Brazil began by imposing the logic of private appropriation and expropriation of indigenous and traditional territories. The long period of hereditary captaincies and sesmaria (royal) land grants, which culminated in the enactment of the first Brazilian land law, reinforced that mindset. This was the thinking behind the Land Law adopted in 1850, which excluded and expropriated peoples from their territories, based on racist conceptions shoring up the white hegemony of the landowning class. The Land Law introduced criteria to transfer public lands to private owners in a minimally “regulated” manner. It prioritized, in theory, the legitimation of productive uses of lands, and established the fundamental premise that Brazilian lands have public origins.

As it turned out, however, not even the expeditious criteria provided by the Land Law were enforced, and land-holding elites to this day have been unable to carry out a conventional process of transferring public property to private ownership. This explains Brazil’s so-called “land-tenure chaos”, marked both by the presence of old, but absolutely tainted, property titles that do not prove the passage of the land from public to private ownership, and by more recent titles for large rural estates, created or rigged in notary publics’ and politicians’ offices, often with the use of violence, many of them legitimized by the Judiciary. The deeper we delve into scrutinizing titles to large land holdings in Brazil, the more flaws we find suggestive of orchestrated action by public and private players for the illegal, private appropriation of public lands. The history of illegal land appropriation also intertwines with the appropriation and restriction of public policy spaces by powerful groups negotiating behind closed doors.

Since the 1960s, a crucial time in the expansion of agricultural frontiers into the Amazon and Cerrado regions, successive laws have been enacted to validate irregular titles, to facilitate the “creation” of new titles, or to foster the implementation of policies that promote the conversion of public lands – or lands long held by traditional communities – into private lands. The federal Land Statute enacted in 1964, the law on boundary (ações discriminatórias) determinations and various state laws introduced since then do contain a few criteria and limitations to the transfer of land, but their main use has always been to legitimize illegal appropriations.

This process has intensified since the turn of the century with the “commodities boom”, as primary products, especially grains and minerals, have emerged to account for over half of Brazilian exports, while commodity prices also surged on world markets. When this scenario intensified demand for land in exporting countries, it also heated up real estate markets and land speculation. It was in this context that, in violation of the Federal Constitution, Law 11,952 – also known as the “Land Grabbing Law” (Lei da Grilagem) – was approved in 2009, creating the federal Legal Land Program, to expedite the regularization of recent irregular land takeovers in the Legal Amazon region, of up to 1,500 hectares each. Soon after, in 2012, Congress passed the new Forest Code, for the environmental regularization of rural properties through amnesties or pardons for environmental offenders (who were no longer obliged to restore Legal Reserves and Permanent Preservation Areas [APPs] on their farms) and through the legalization of areas recently deforested to expand agricultural frontiers. It also authorized for the first time the transfer of native vegetation from the commons system to private property, through the creation of Environmental Reserve Quotas (CRAs), which must be listed on stock exchanges.

Although Brazilian land history has always revealed close connections between land laws, the accumulation of wealth by a small white landowning elite, and the ensuing promotion of violence in the countryside, the last five years have exposed this nexus as never before, intensified by the global race for land coupled with a growing interest by large financial corporations in garnering strategic stocks of debt collateral.

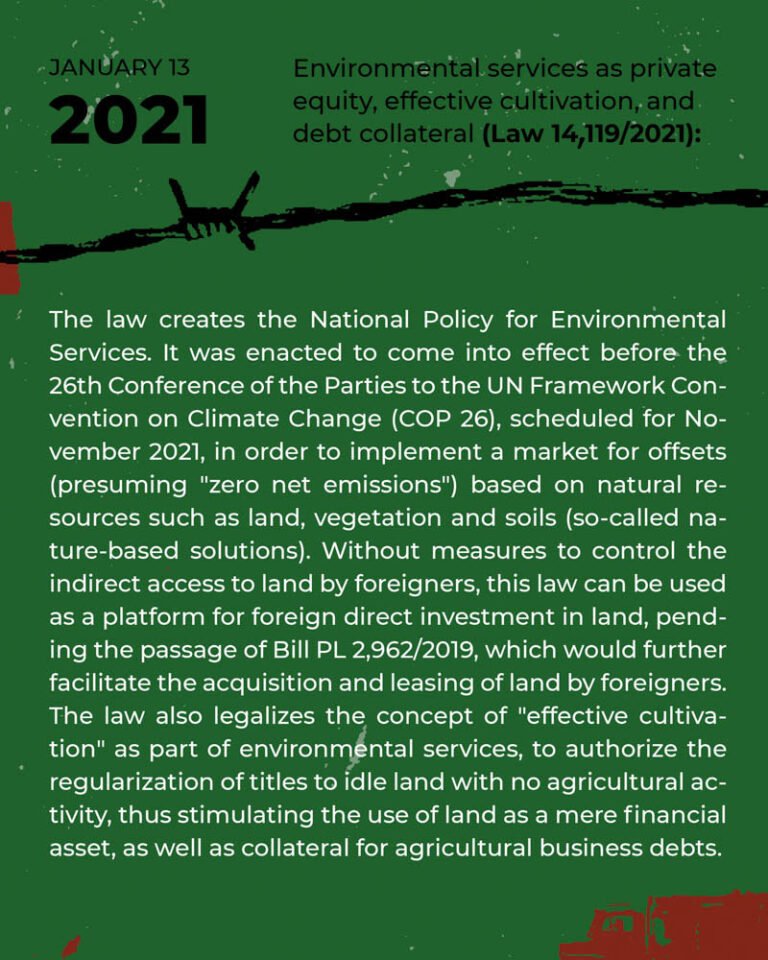

The institutional and political coup that deposed President Dilma Roussef in 2016, followed by the irregular government of Michel Temer, and later the election of Jair Bolsonaro, created a political environment even more conducive to the accelerated passage through Congress, with no consultations with society, of bills designed to privatize and denationalize the land, along with other legal measures to promote the interests of the national agrarian bourgeoisie and international capital. It is no exaggeration to say that the legislative changes promoted in this short period of time, as well as those still in the pipeline, are more drastic and devastating than anything that happened in the last five hundred years. Since the approval of Law 13,465/2017 (MP 759/2016), also nicknamed a “Land Grabbing Law” – which authorized a massive transfer of federal public and unclaimed property to large landowners (up to 2,500 ha) – various new laws and regulations approved since 2016 are part of a veritable offensive aimed at the private appropriation of land and nature and at ensuring legal certainty for landowners, rural producers, and investors.

Land use and occupation patterns between the countryside and cities, the concentration of land and natural resources, the massive destruction of ecosystems, and the increasing homogenization of landscapes have been singled out among major structural causes for the outbreak of epidemics and their accelerated spread into pandemics. The reworking of Brazil’s land tenure fabric enabled by Law 13,465/2017 and other pieces of legislation referenced in the timeline promise an unprecedented concentration of rural land, with the ensuing expansion of deforestation and habitat destruction and the incorporation of land use and occupation by this industrial scale of commodity production, all culminating in an escalating expulsion of thousands of peasants, peoples, and communities to urban peripheries. The industrial production of rural and urban spaces is a cauldron for future pandemics and health crises.

We have no doubt that this legislative locomotive can only be halted by organizing solidarity among peoples, from their local territories up to an international scale. On the one hand, workers in the Global North who see their pension fund contributions going to illegal land purchases that evict peoples of the Global South from their territories, have the veto power to demand the withdrawal of such destructive investments. On the other hand, resources essential to dignified lives for present and future generations, such as biodiversity and water, are still in the ancestral possession of traditional peoples and in public lands that belong to all of society. Therefore, an appropriate response to the challenges imposed by the massive privatization of the commons, land, and natural resources will necessarily include ways to reproduce the livelihoods and survival strategies fostered and implemented by the many peoples, communities, and movements who make up the diversity and promote the biodiversity of the Brazilian countryside and who, by no coincidence, are the priority audience for the fair distribution of Brazil’s public lands.

Be it for the historical debt, be it as a constitutional mandate or through structural measures to contain the aggravation of our overlapping ecological and sanitary crises, a national popular uprising and international solidarity to defend public and common goods is more necessary than ever, to distribute Brazilian lands in favor of the territorial rights of rural peoples. The remedy against future pandemics lies precisely in societies being able to implement structural measures to deconcentrate and distribute land to those who want to work it, while protecting biodiversity, habitats, and associated productive livelihoods. This all begins with a simple step: the unity of the working class and the peoples’ struggle against market-driven land regularization projects.

References

AATR, ABRA, CPT, GRAIN. Caderno “Do golpe político ao golpe fundiário”, 2020.

AATR. Legalizando o Ilegal, 2020.

Larissa Packer. Elementos para se compreender o contexto socioambiental e fundiário brasileiro: Agronegócio, desmatamento e caldeirão de futuras pandemias (mimeo). 03.02.2021.

Coordenação Nacional de Articulação das Comunidades Negras Rurais Quilombolas – CONAQ e Terra de Direitos. Racismo e violência contra quilombos no Brasil. 2018.

Observatório do Clima. Passando a Boiada. O segundo ano de desmonte ambiental sob Jair Bolsonaro, janeiro de 2021.

Britaldo Soares-Filho; Raoni Rajão; Marcia Macedo; Arnaldo Carneiro; William Costa; Michael Coe; Hermann Rodrigues; Ane Alencar. Cracking Brazil’s Forest Code. Science 25 Apr 2014:Vol. 344, Issue 6182, pp. 363-364.

Joice Bonfim is a lawyer for social movements and coordinates the AATR. She holds a Master’s Degree in Social Sciences, Development, Agriculture and Society from CPDA/UFRRJ.

Larissa Packer is a socio-environmental lawyer with a Master’s Degree in Philosophy of Law from UFPR. She is a member of Grain’s Latin America team.