Rondônia

AMAZÔNIA

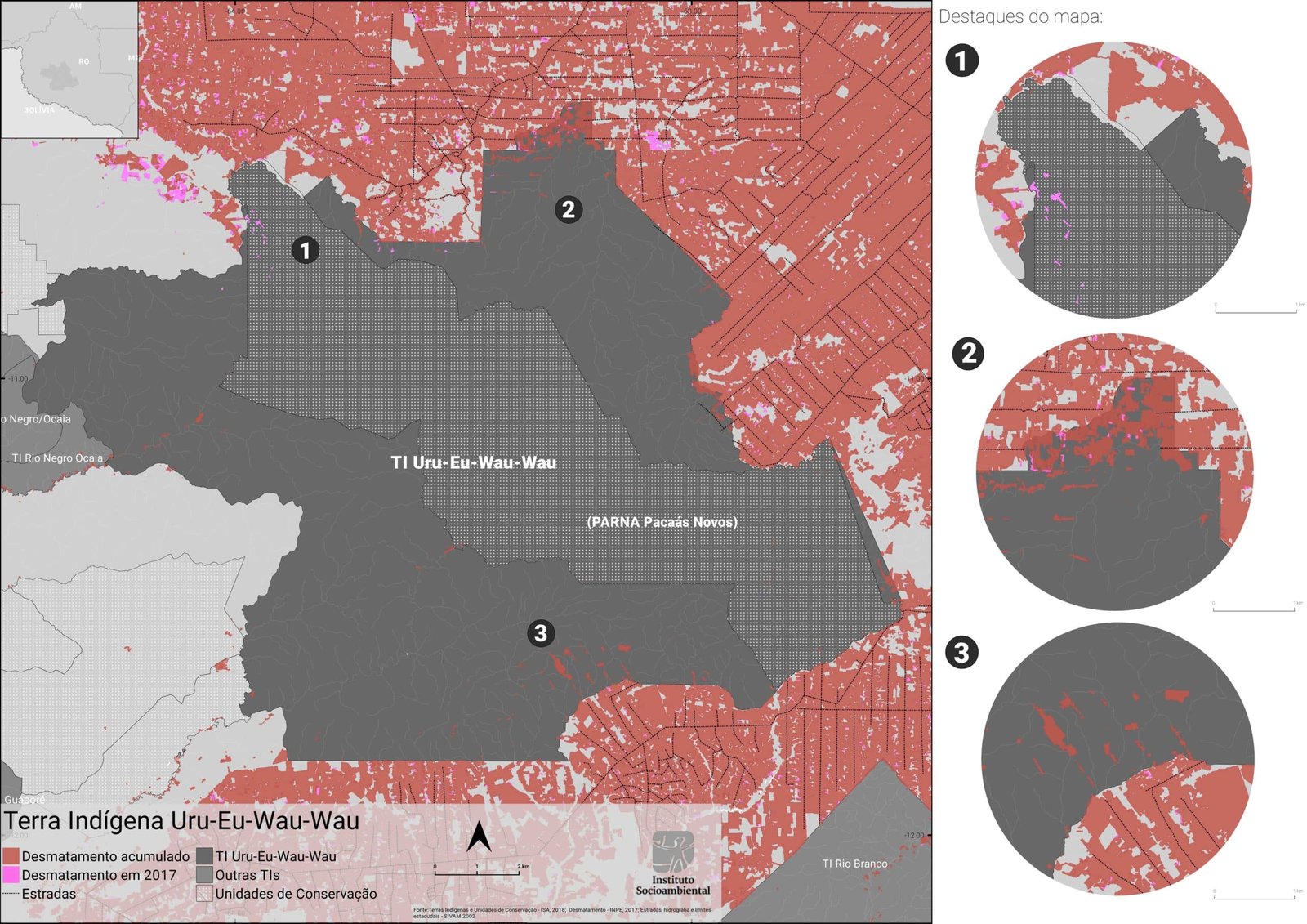

The territory of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous people, self-named Jupaú, is located in the Brazilian Amazon and for decades has faced threats and violence caused by invaders within its boundaries. Located in the state of Rondônia, it covers the municipalities of Alvorada D’Oeste, Cacaulândia, Campo Novo de Rondônia, Costa Marques, Governador Jorge Teixeira, Guajará-Mirim, Jaru, Mirante da Serra, Monte Negro, Nova Mamoré, São Miguel do Guaporé, and Seringueiras.

It lies on part of the Serra dos Pacaás Novos mountain range, which contains the highest point in Rondônia, known as Pico do Tracoá, and on part of the Serra dos Uopianes. The territory covers a total of 1,867,117 hectares. The Pacaás Novos National Park, established in 1979, overlaps 711,920.29 hectares of the indigenous land, 37.95% of its area. It is estimated that 209 indigenous people currently live on this land[1], including the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, Amondawa, OroWin, and isolated groups known as Yvyraparakwara, Jururey, Baixinhos, and a fourth, whose name is unknown.

Encroachment on the indigenous territory intensified in the 1980s as a consequence of the settlement process and expansion of agricultural and cattle ranching frontiers into the interior of the state of Rondônia. Despite the prolonged conflicts, with great insecurity and fear on the part of its indigenous people, the territory was declared the permanent possession of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau people in 1985. That status, however, was revoked in 1990, but reestablished in 1991, when the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous Land (IL) was registered and ratified by a decree issued by then-president Collor[2], after a long dispute involving the National Indian Foundation (Funai), the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra), and the Brazilian Forest Protection Institute (IBDF). These government agencies had different projects and interests for the area due to the colonization process[3].

Despite the recognition of indigenous rights and the ratification of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous Land in 1991, unceasing territorial conflicts[4] have involved different social groups, such as rubber tappers, farmers, garimpeiros (illegal miners), loggers, and cattle ranchers, in addition to the State and economic agents involved in development projects for the region. The invaders also mobilize a variety of strategies to take over the territory and its resources, such as deforestation, garimpo (illegal mining)[5], arson, Brazil nut theft and the felling of the nut tree stands, predatory hunting and fishing, and land grabbing.

Notes

More information on the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous Land. Accessed on March 09, 2022.

More information in the report: “Missão de levantamento de informações sobre a terra indígena Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau”, published in December, 2020, by the National Human Rights Council (CNDH). Source here. Accessed on March 14, 2022.

More information at:

“RO – TI Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau sofre constantemente com grandes obras públicas e ações do agronegócio” Accessed on March 14, 2022;

“Centenas de invasores entram na Terra Indígena Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau e preparam derrubada da floresta”; Accessed on March 07, 2022;

“Guerreiros Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau relatam como expulsaram grileiros da terra indígena”; Accessed on March 07, 2022;

“Indígenas do povo Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau são pressionados por extração ilegal de madeira”. Accessed on March 07, 2022.

An aggravating factor in this situation has been the more than 30 years of infighting between Funai and Incra, related to a resettlement in an area covering 18,000 hectares that overlaps the Indigenous Land[6]. It is a consequence of the improper issuance, in 1980, of approximately 113 final tenure titles to settlers inside the Indigenous Land, as part of the Burareiro Directed Settlement Project[7]. Today, indigenous leaders claim that 70 percent of Burareiro is completely deforested. Meanwhile, deforestation of the Indigenous Land is advancing into other locations as well, beyond the Burareiro project.

Bitaté Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, a young indigenous leader, makes this denunciation:

Conflict and fears intensify

In the past three years, this long-standing, conflict-ridden panorama intensified with the political organization of local farmers and cattle ranchers[8]. Indigenous leaders say that the so-called Marechal Rondon Ranch, which borders the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Land, was occupied, and used as an access route to invade indigenous territory, and the raiders are still there. On that occasion more than 300 hectares of Brazil nut tree stands were cleared and fenced off. The timber from the deforestation was stolen and sold, and the area converted into cattle pasture.

The main harm from the violence plaguing the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau has been the damage to their well-being and a feeling of insecurity throughout the territory, due to constant tensions for the indigenous people, under recurring threats.

One unforgettable tragedy was the death of Ari Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, found with marks of beatings all over his body, at the age of 33, on the night of April 18, 2021[9]. Indigenous leaders suspect that Ari’s murder is related to the invasions[10]. They also denounce that, on that occasion, even the funeral ritual – which consists of a march with songs through the forests of the territory – could not be performed by the elders, due to the presence of intruders. Ari was active as a guardian in the people’s independent territorial monitoring actions, organized by the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau themselves in response to invasions and violence in their territory.

As things stand, the indigenous people are constantly subjected to the sound of chainsaws and tractors, which disrupt their peace and quiet even inside the villages. And they know that the intruders come in armed. In their day-to-day routines, therefore, they face the real possibility of attacks and all kinds of violence as they walk through their own territory.

The situation is even worse for isolated indigenous peoples, all the more so in times of a pandemic. Contact with Covid-19 infected invaders can trigger a genocide.

The feeling of constant insecurity makes the elders relive traumas, especially women who resisted other attacks following contact with the fronts’ encroachment in the 1980s. They are very afraid that the intruders will attack the villages at night to kill everyone, as has happened before. One elderly woman, who survived a massacre in her village as a young girl, bears marks and feels pain in her body in places she was wounded decades ago by the invaders’ gunshots. Fearful, she questions why her people still endure this kind of violence today, in an ongoing process of invasions stemming from impositions by agents of both state and economic interests over their territory and its resources.

The older men also worry about how intrusions threaten the safety of their families and the village as a whole, as one of the indigenous leaders, whose name we will keep confidential, explains:

Notes

More information at:

“Terra Indígena Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau está livre de intrusos, mas novas invasões poderão ocorrer”. Accessed on March 14, 2022;

”PF desmonta esquema de grilagem que causou prejuízo ambiental de R$ 22 mi na terra dos índios Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau”. Accessed on March 14, 2022.

More information at “Indígenas impedem invasão de grileiro na Terra Indígena Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau na Amazônia”. Accessed on March 14, 2022.

More information at “‘Retrato de um ano trágico’: mortes de Ari Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau e Rieli Franciscato são lembradas em relatório do Cimi”. Accessed on March 09, 2022.

More information at “Quem matou Ari Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau? Morte de guardião de território em RO completa um ano”. Accessed on March 14, 2022.

Damage to livelihoods and fires

As described in the victims’ own accounts, territorial conflicts also cause environmental damage such as deforestation, fires, garimpo/illegal mining, loss of riparian forests, pollution of rivers, and death of animals, while compromising food security and the quality of life in the territory. Indigenous leaders estimate that, by 2019, 18,000 hectares had been deforested in the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau Indigenous Land. In 2022, that figure reached 25,000 hectares.

Environmental impacts, in turn, compromise other dimensions of a people’s way of life, like the felling of Brazil nut trees in managed stands. Brazil nuts are a source of income and food for the indigenous people – as well as for wild animals – and an important element in their cosmology. They are linked to the performance of rites and festivities, such as weddings and the “Little Miss” (Menina Moça) feast, a celebration in which the “Botawa” is served, a kind of “cultural cake of the indigenous people”, in the words of a leader, made from boiled and peeled green Brazil nuts, pounded in a pestle, and mixed with roasted boneless fish. The felling of Brazil nut stands in areas close to the villages makes it hard for the indigenous people to maintain their traditions.

Furthermore, as the invaders move in, typically by clearing and burning the plant cover, the hunting and fishing prey retreat to distant areas of the territory. Indigenous people then have to travel farther for their subsistence activities such as farming, hunting, extractivism, and fishing. Longer distances take more time and impose greater risks, impacting their work in the fields and the time left for festivities and other dimensions of social life.

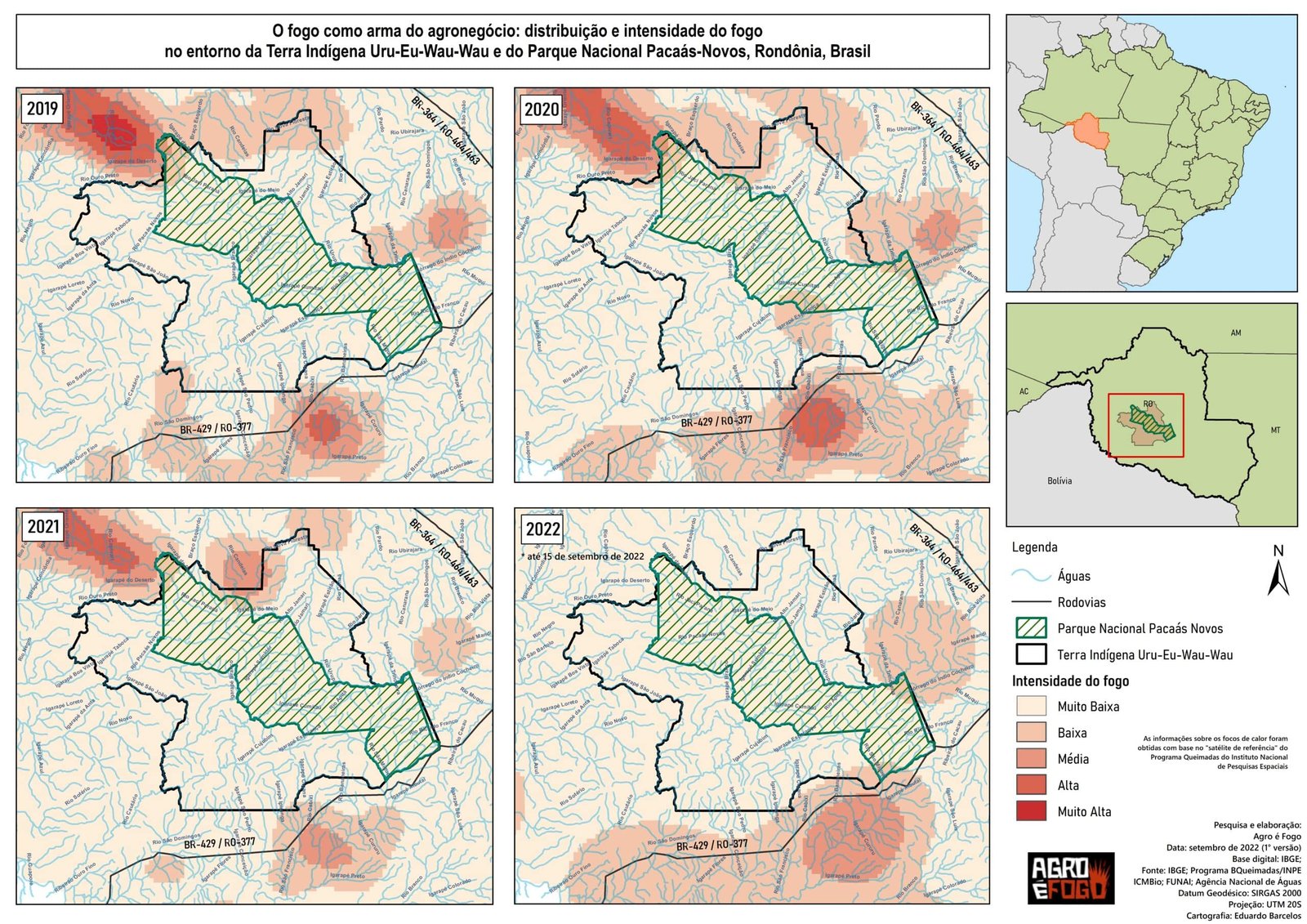

During the invasions, fire is an essential element for invaders to achieve their ends. After entering the territory, the land grabbers’ next step is to deforest the land and set it on fire, to open it up for cattle and soybeans. This land-grabbing cycle has been reported in the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau territory since at least 2016[11] when indigenous people denounced landowners and politicians who were encouraging new invasions of the territory. Related to this case, aerial images identified the large scale of burned areas.

In 2019[12], fires were set again, in the area where the Pacaás Novos National Park overlaps the Indigenous Land. To stop the spread of those fires and new burnings, Ibama inspectors and military police officers identified about twenty armed land grabbers inside the territory on August 13 of that year. Later, in September, the Federal Police had twenty court warrants issued against the land grabbers responsible for the fires.

Territorial protection

In an effort to protect their land from criminal invasions, the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau indigenous people have for some years now been doing an independent territorial monitoring, to ensure the constant surveillance of their territory. The work is done by the indigenous people themselves, divided into two fronts. The first is the vigilance they perform during their daily activities, such as hunting, fishing, and farming, as they move around the whole area. When anything suspicious is detected, or a new invasion is observed, the official surveillance team is called to take the appropriate measures.

The second front of the initiative, on the other hand, involves so-called “guardians”, who carry out scheduled and larger-scale surveillance actions, when the indigenous team sweeps suspected invasion areas, using trucks, drones, cameras, and GPS. When they identify an invasion, the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau do not engage in direct conflict with the invaders, but rather mobilize the Funai to intervene.

In the words of Bitaté Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau:

The threats persist. In October 2020[13], the arson was so big that even the indigenous people’s monitoring with drones was compromised. The smoke made it difficult to locate and map the invaders: “The drone goes up 40 meters and the smoke doesn’t let us see anything”[14], said Bitaté Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau. Despite this, they managed to spot areas the size of two soccer fields burned by invaders and newly cleared areas ready to be turned into pastures.

Notes

Jornal Rondônia Dinâmica. Oct. 28, 2016. Tribo gavião-real e seus vizinhos isolados enfrentam aniquilação na Amazônia. Available in the archives of Dom Tomás Balduíno Documentation Center – CEDOC/CPT.

G1 Globo. Sep. 17, 2021. PF descobre advogados e topógrafos ajudando grileiros no desmatamento de parque e terra indígena, em RO. Accessed on April 11, 2022; O GLOBO. Aug. 30, 2019.

Parques nacionais e terras indígenas queimam em Rondônia. Accessed on March 11, 2022 ; G1 GLOBO. Sep. 19, 2019.

Dois investigados na Operação Terra Protegida em RO continuam foragidos. Accessed on March 11, 2022. PROJETO COLABORA. Sep. 17, 2022.

Madeireiros derrubam árvores e ameaçam indígenas em Rondônia. Accessed on March 11, 2022.

CONSELHO MISSIONÁRIO INDIGENISTA. 14/08/2020. Solidariedade partilhada: nas aldeias ou em contexto urbano, indígenas enfrentam muito mais do que o avanço da covid-19 em Rondônia. Accessed on April 11, 2022. ; Instituto Socio Ambiental. 09/03/2020.

Covid-19 se espalha em Rondônia e indígenas lançam mensagem de resistência. Accessed on April 11, 2022.

CORREIO BRAZILIENSE. Nov. 11, 2020. Abandonadas pela Funai, 60% das terras indígenas são devastadas por mais de 100 mil focos de incêndio. Accessed on April 11, 2022

In September 2021, the Jupaú Association’s monitoring team[15], accompanied by other indigenous people, went to a burned area identified by satellites. There they found that “invaders burned the forest to put thousands of cattle on top of an ancestral indigenous cemetery,” as the indigenous Txai Suruí had denounced. Earlier deforestation had occurred in the north of the territory, in the area called Burareiro[16].

All the work to plan protection actions and then manage data after monitoring invasions, in addition to preparing material and denunciations for political advocacy, done independently by the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau people and the Jupaú Association, in practice competes with the time to do their other work, rest, and leisure activities, highlighting the seriousness of the conflicts.

Institutional delays

The time spent by indigenous people producing and organizing documents for accusations is not always rewarded by aid and efforts from agencies responsible for addressing conflicts. In general, the response they get is sluggishness, underfunding, and disinterest on the part of Funai, the Brazilian Institute for the Environment (Ibama), the Chico Mendes Institute for Conservation and Biodiversity (ICMBio), and the Federal Police.

This political omission by official inspection and territorial protection bodies inspires more invasions. In 2018, Awapu, then president of the Jupaú Association and threatened with death by invaders, told reporter Nahama Nunes of Radio Brasil Atual that the indigenous people had denounced the conflicts for some time and were demanding help from Brazilian authorities[17].

The length of the most recent invasion of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau IL, which began more than three years ago, is one example of those bodies’ inefficiency. Leaders report that, after the first movements by invaders, the indigenous people began to send photographs taken by drones, with GPS coordinates, to the Funai, which should have called in the Federal Police to officially remove the invaders. Instead, Funai postponed its visit to investigate the site, and when it did, it did not request support from the Federal Police. The invaders were not removed, and the invasion is still there, as a daily threat to the lives of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau.

Even when the authorities acknowledge accusations and take some surveillance action, the indigenous people consider that their isolated actions are not effective in clearing the areas and holding invaders accountable.

Bitaté Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau continues the story:

Despite the challenges they have faced for decades, with recurring invasions and lack of or insufficient support from the State, the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau people have historically found strategies to ensure the ongoing reproduction of life in their territory, which is abundant in sociobiodiversity[18], cosmologies, and traditional knowledge. As part of their resistance, they developed monitoring and territorial surveillance as tools to respond to daily adversities, inspired by their traditional practices, such as the long walks their ancestors took throughout the territory. Through such efforts to care for life and ensure respect for territorial rights already won, the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau hope that “our future generations will be aware of what we have already been protecting. And that they will know the history of our ancestors, who also fought to protect what we have today,” concludes Bitaté Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau.

Notes

TXAI SURUÍ. Nov. 26, 2021. Instagram post. Accessed on: April 11, 2022; G1 GLOBO.

Txai Suruí denuncia criação de gado em cima de cemitério indígena em Rondônia. Accessed on: April 11, 2022; Instituto Socio Ambiental. Sep. 30, 2021.

SISTEMA DE ALERTA DE DESMATAMENTO EM TERRAS INDÍGENAS COM REGISTROS CONFIRMADOS DE POVOS ISOLADOS. Available in the digital archives of the Dom Tomás Balduíno Documentation Center – CEDOC/CPT; G1 GLOBO. Nov. 04, 2021.

Terra Indígena com povos indígenas isolados em RO têm alta de 583% no desmatamento em setembro, diz instituto. Accessed on: April 11, 2022.

“Em Rondônia, indígenas denunciam invasões e ameaças de morte”. Accessed on April 26, 2022.

Tainá Holanda Caldeira Baptista and Kena Azevedo Chaves are researchers at the Center for Sustainability Studies of the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGVces).

Ivaneide Bandeira Cardozo is an expert in indigenous affairs at the Association for Ethno-environmental Defense – Kanindé.