Amazônia

RONDÔNIA

The Karipuna of Rondônia state[1], who call themselves the Ahé – meaning “real people” – had their Indigenous Land (IL) officially approved by the federal government in 1998, covering 153,000 hectares in the municipalities of Porto Velho and Nova Mamoré. It is one of 26 ILs in the state of Rondônia. More than 20 years later, however, the Karipuna’s land is still not free from threats. In 2018, the situation actually became a “powder keg,” as Adriano Karipuna, spokesperson for his people, characterizes it[2].

The Karipuna IL has suffered mainly from landgrabbers and loggers, who, on one hand, burn, destroy, invade, and steal the land’s different forms of wealth, and, on the other hand, seek to legalize their criminal activities and have their crimes recognized by the constitution. The pressure behind all this is agribusiness, which smothers other forms of life and relationships with sociobiodiversity.

This reality is also present in neighboring territories. The Karipuna IL is part of an ecological corridor populated by peoples in isolation, riverside communities, and other traditional communities. This corridor includes the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau[3], Igarapé Ribeirão, Igarapé Lage, and Pacaás-Novas Indigenous Lands; particularly, the Jaci-Paraná Extractive Reserve (Resex) and the Guajará-Mirim Park border the Karipuna territory.

Notes

People’s wealth threatened for centuries

The Karipuna Indigenous Lands are delimited by natural boundaries, such as the Jaci-Paraná river, the Formoso river and the Fortaleza, Juiz and Água Azul streams (igarapés). It is possible that the Karipuna migrated from the upper Tapajós River to the current region in the 17th century. However, the oldest records of contact of the Karipuna people date from the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, as one of the effects of three decades of intense rubber extraction for export[4].

Between 1868 and 1912, a 366 km railroad – known as “devil railway” – was built connecting Porto Velho to Guajará-Mirim, on the border with Bolivia. It was a catalyst for the expansion of villages and for a significant increase in the population of non-indigenous segments in the region, and gave rise to the city of Porto Velho itself. Adriano reminds us that it is not the indigenous peoples who go to the cities, it is “the cities that go to the Indigenous peoples”.

Starting in the 1950s, federal and state government projects, such as highways and railroads, gained momentum. Meanwhile, the lives of the native peoples and traditional communities in the region became more restricted and threatened. Because of the occupation frontier encroachment upon northlands and the establishment of contact, the Karipuna had been reduced to only 8 people by the end of the 20th century. “After contact, many diseases appeared, but before we were many and healthy,” recalls Katiká Karipuna, one of the few survivors of her people[5].

The official recognition of the IL was a victory, but even this official federal ruling did not succeed in stopping the violence[6]. Conflicts in the IL have been reported since at least 2009. In the past 16 years, there have been only six operations in the region (three of them since 2019) by enforcement authorities such as the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), police officers, and the National Indian Foundation (Funai)[7]. In addition, the annual report by the Indigenist Missionary Council (Cimi) based on data from 2021 found that the indigenous peoples of Rondônia are among the most affected by crimes and violence. The Karipuna IL, along with the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau territory, is at the top of that list[8].

Katiká Karipuna[9]

“Does anyone set their own home on fire?”: fires and deforestation go hand in hand

The situation has become increasingly critical when former President Jair Bolsonaro took office with his deceitful and inflammatory rhetoric and cutbacks in funding for enforcement agencies. In 2022, he accused traditional peoples and communities of being the primary culprits for fires in the Amazon. He said that fires occur naturally in this region[10], and, speaking at an international event, he said that, because it is wet, the rainforest doesn’t catch fire[11].

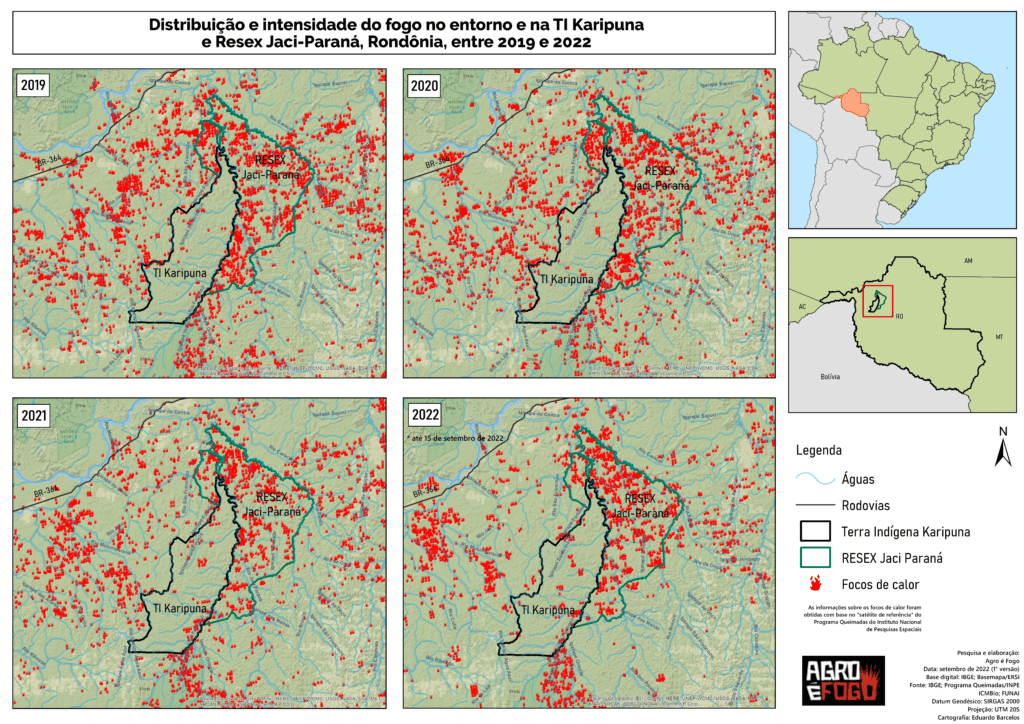

Deforestation in Rondônia continued to spread and the Karipuna IL was one of the 20 most affected in all of Brazil from January to April 2020. By no coincidence at all, its ranking in 2019 had also made it the IL with the most fires in Brazil[12].

The invasions expanded during the pandemic, which for former minister Ricardo Salles provided the government with cover to “drive the herd through the gate”[13]. From January to August 2021, in Rondônia, there was a 47% increase over the previous year in the number of fires, and 40% of all the fires in the state were in the municipality of the capital, Porto Velho. While in 2020 there were 24 fires within the Karipuna IL, in 2021 the figure more than doubled to 62[14]. The Karipuna have felt the weight of the Minister’s “herd” stampeding through.

2022 has been no different. During the Amazonian summer (the dry season, June to November), the number of fires was alarming: in the first five days of September, two new hot spots were reported every minute, for a total of 14,839 throughout the region. Porto Velho ranked fifth among the municipalities with the most fires in the month of July in all of Brazil. It is no wonder that some people call this state capital the “Brazilian fire capital”[15].

In addition to criminals setting forest fires in the Karipuna IL as one phase of their deforestation cycle, fire is also used as a weapon of terror[16]. In 2018, the Funai surveillance post, 12 km away from the only village in the IL, was set on fire by invaders who, a year later, had still not been identified[17].

Notes

Although it is not known for certain whether the Karipuna of the past are the same as those of today, it is certain that the region was occupied by Kawahib groups, such as the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, Amondawa, Tenharim, and Parintintin peoples, with whom the Karipuna share certain cultural similarities. To learn more, see. Accessed on August 5, 2022.

Povo Karipuna resiste à destruição de suas florestas (video in Portuguese, Greenpeace, 2018)

During the identification process and the formal registry of the IL, the south of the territory was invaded as soon as the area of 195,000 hectares was closed off by Funai. The invaders took possession of a strip near the BR-421 highway (Ariquemes/Guajára-Mirim) and, at the request of INCRA and the Rondônia government, the Funai compromised on finally approving 153,000 hectares, in exchange for conditions and impositions by Funai that were never implemented. For more details about the contact process, see.

A luta do povo Karipuna para não desaparecer na Amazônia (DW, 8/07/2022)

Studies show that 60% of the fires in the Amazon in 2021 were not caused naturally. The main culprits behind fires in the Amazon are interested in expanding crops and pastures into the northern lands of the country. Available here.

Bolsonaro diz que ribeirinhos contribuem com queimadas na Amazônia: ‘Toca fogo na sua pequena propriedade’ (TV Cultura, Aug. 22, 2022) and Em Dubai, Bolsonaro diz: “Amazônia, por ser uma floresta úmida, não pega fogo” (CNN, Nov. 15, 2021 )

Porto Velho concentra 40% dos focos de queimadas em Rondônia – Amazônia Real (Amazônia Real, Aug 26, 2021)

Information: Porto Velho foi a 5ª cidade do país com mais focos de queimadas em julho, aponta Inpe (G1 RO, July 29,2022), 2 focos por minuto: Amazônia alcança maior taxa de queimadas da história (UOL, Sep 8, 2022) e Amazônia em chamas, uma radiografia de fogo e violência em Rondônia (El País, Sep 12,2021)

See also in this dossier the article “Weapons in the battle for territorial control: capitalistic uses of fire against rural peoples” [colocar link]

Invasores ateiam fogo em Posto da Funai localizado na TI Karipuna (Cimi, Feb 11, 2018)

In the past, the northwest region of the Karipuna Indigenous Land was the most affected, but recent years have seen more invasions in the southeast, near the Formoso River. From 2020 to 2021, this region was responsible for 65% of new deforestation in the territory[18].

Videos available on the internet reveal the invaders’ audacity. Along the trails and cleared areas, we see logs with high market value lying on the ground, waiting to be trucked out to their unlawful destination. The timber is even processed on site[19]. The scale of the felling, the speed, and the violent action of the criminals reveal the magnitude of these invasions, which demand huge financial investments.

There are other indications as well of connections between deforestation and land grabbing. The Rondônia government’s own estimate of the number of cattle in protected areas around the Karipuna IL is an alarming 150,000. Even more intriguing is that, despite being “illegal”, this livestock is vaccinated and monitored by state animal health agencies[20].

In addition, in 2019, an organized land-grabbing operation was launched to sell plots of land in the Karipuna IL, in which georeferencing companies were acting to give the impression that regularization was imminent. The Rural Environmental Registry (CAR), self-declaratory, has been used with no legal basis to legalize rural landholdings. In 2019 alone, according to data from the Federal Prosecutors’ Office (MPF), more than 90 areas within the Karipuna IL had been registered. A Greenpeace survey showed that a total of 2,600 hectares were registered as CAR from 2015 to 2019[21].

The year 2022 began with new denunciations of land grabbing practices and illegal logging in the Karipuna IL. Land grabbers feel secure and protected as they proceed unpunished within the territory, leaving trails of destruction and threatening the physical integrity of the surviving members of the Karipuna people, their leaders, and their allies.

Where is the State in all this

Adriano Karipuna holds the Brazilian State responsible for the invasions. According to him, by opting for a type of development that is “bloodthirsty, murderous, that destroys culture, languages and even the forest”, the State has “an unredeemable historical debt” towards the indigenous peoples.

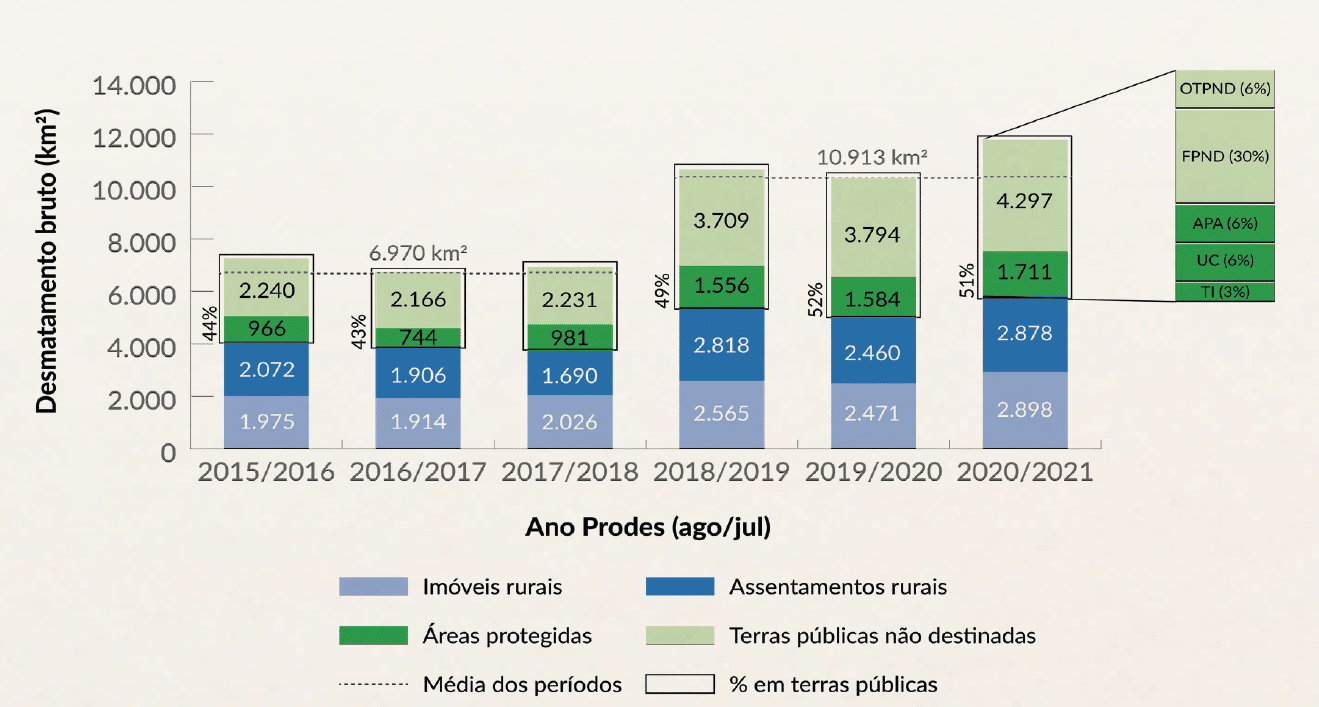

Data from the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) from August 2020 to July 2021 placed Rondônia in second place in the deforestation of protected areas: 12% of all land deforested in this category. This data is not isolated. In the other land category, non-allocated public lands, Rondônia, together with Pará and Amazonas, accounted for 82% of deforestation in the entire Amazon region[22].

State governments have been facilitating agents for these crimes. Laws passed by the Legislative Assembly of Rondônia legalized and regularized several invasions, reducing the protected areas in the state, and this has been fatal for indigenous peoples and traditional communities. In 2021, Governor Marcos Rocha approved complementary law n° 1,089, which removed almost 170,000 hectares from already highly threatened protected areas bordering the Karipuna Indigenous Territory – the Jaci-Paraná Resex and the Guajará-Mirim State Park – provoking even more invasions.

The Jaci-Paraná Resex is overrun with pastures. When it rains … all the water runs right through the farms and into the Jaci River, totally contaminated with pesticides. The indigenous people and riverside dwellers then catch and eat the contaminated fish that live in the water. So, there are countless contaminations happening, countless disasters.

The year before, 2020, something else had boosted the advance of loggers and invaders: the approval of Bill 85/2020, which amended the Ecological Economic Zoning (ZEE) law. This fact intensified the takeover of areas near the IL, allowing already deforested areas to be exploited. At the same time that fires and deforestation advance, agribusiness is also expanding. In the past 10 years, cattle ranching and soy farming have grown dramatically in the state. Livestock production increased 87% in the municipality of Porto Velho alone, and the area for soy farming more than tripled – from 111,000 hectares to 400,000 hectares in 2020[23].

The Karipuna IL, located just a few kilometers from the capital Porto Velho, is located in a strategic “logistical distribution center” for agribusiness. That is why federal and state highways, hydroelectric complexes and ports on the Madeira River are considered priorities for the state, to the detriment of indigenous and traditional communities.

Notes

Carne e soja pressionam a Terra Indígena Karipuna (Greenpeace, Oct 26, 2021)

See Povo Karipuna resiste à destruição de suas florestas (Greenpeace, 2018) and A luta do povo Karipuna para não desaparecer na Amazônia (DW, 2022).

Povo Karipuna denuncia incêndio criminoso provocado por madeireiros e grileiros em seu território (InfoAmazônia, Aug 19, 2022)

See: PF faz operação para prender 9 suspeitos de provocar queimadas na Terra Indígena Karipuna, em Rondônia (G1 RO, Oct 7, 2020), Queimadas e invasões cercam e ameaçam povo indígena Karipuna: ‘Estamos sós’ (UOL, 10/09/2022) and Povo Karipuna processa União, Funai e estado de Rondônia por invasões e devastação da terra indígena (Greenpeace, 05/05/2021)

Amazônia em Chamas 9 – O novo e alarmante patamar do desmatamento na Amazônia (IPAM, Feb 2, 2022)

Carne e soja pressionam a Terra Indígena Karipuna (Greenpeace, Oct 26, 2021)

The Karipuna people’s ways of (re)existing

In 2018 and 2019, mobilizations by Karipuna leaders, together with the Indigenist Missionary Council and Greenpeace, showed that it is possible to contain invasions and deforestation[24]. International denunciations had significant impacts: in 2018, at the 17th Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues; in 2019, at the 41st Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council; and, in 2020, at the Amazon Synod, organized by the Vatican[25]. By 2022, Adriano had visited more than nine countries denouncing the situation for people living near Porto Velho.

Even now, I believe in my children and my grandchildren. They are still small, but they will fight for this place in the future. I am already a grandmother, but I don’t lose hope …, even though we are few Karipunas.

Katiká Karipuna[26]

In April 2022, a lawsuit was filed against the state and the Federal Government. In it, the Karipuna demand the urgent removal of invaders, oversight of their IL, destruction of the remnants of crimes that occurred within the territory, in addition to repairing damages, restoration of degraded areas, and the establishment of an effective protection system. The suit also called for the cancellation of all the CARs claiming land inside the IL. On August 10, the Federal Court of Justice ordered the Union and the state to present an “ongoing plan of action for territorial protection” and to reestablish regular inspections[27].

The whole situation has slowed down the process of indigenous population growth and the resumption of cultural practices and rituals. Life as a whole is also threatened, since hunting and fishing are impossible due to the presence of criminals or because the animals have fled the region; trees that provide a certain source of income, such as nuts and açaí, have already been felled; and Karipuna culture itself is threatened. This is also why the Karipuna people promise that they will not give up their struggle.

Notes

Na contramão do caos (Cimi, Dec 18, 2020)

Como o povo Karipuna expulsou criminosos de suas terras na Amazônia – Notícias ambientais (Mongabay, Dec 10, 2020)

Povo Karipuna resiste à destruição de suas florestas (Greenpeace, 2018)

Queimadas e invasões cercam e ameaçam povo indígena Karipuna: ‘Estamos sós’ (UOL, Sep 10, 2022)

Ana Carolina Oliveira is a researcher, with a degree in Anthropology from the University of Brasilia. She has experience in issues related to socio-environmental policies in Brazil, large projects, and the lives of traditional and native peoples. She also works with studies on international cooperation for development.

Laura Vicuña P. Manso works for the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), Rondônia Region.

Our thanks to Adriano Karipuna and Tiago Miotto for their help and participation in this text.