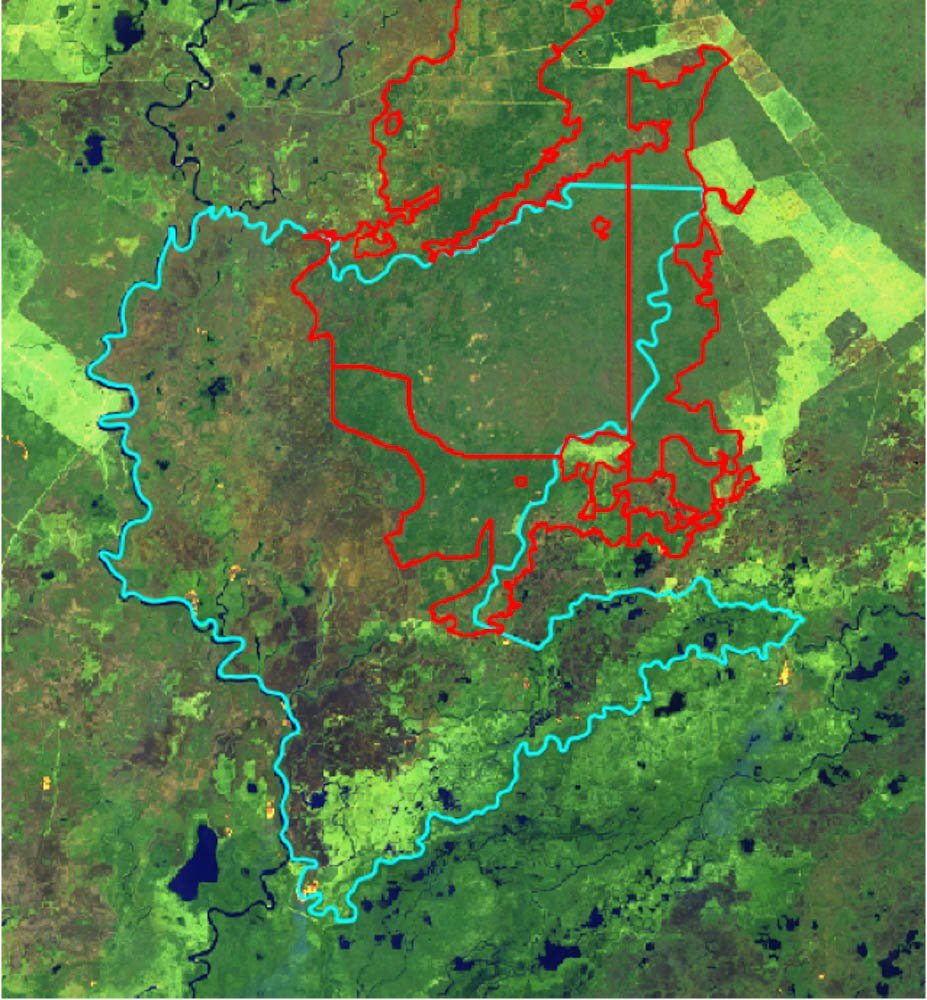

The territory comprising the Kadiwéu Indigenous Land is located in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul (MS), in the municipality of Porto Murtinho, 60 km from the town of Bonito and 425 km from the capital Campo Grande. This Indigenous Land covers 539,000 hectares and is home to approximately 2,000 indigenous Kadiwéu people. The Kinikinau, Terena and Chamacoco peoples also live within this territory, located near the lower Paraguay River basin and overlapping both Cerrado and Pantanal.[1]

Records of the presence of the Kadiwéu in the territory date back to the mid-16th century, in reports from European expeditions prospecting for precious metals in the interior of the country. The records continue and intensify in subsequent centuries, for example in the 18th century with the installation of Portuguese and Spanish military forts in the region. The Kadiwéu are known and respected in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul for their fundamental participation in the Paraguay War, during which this indigenous people claims to have received a document promising protection and “demarcation” from the hands of Emperor Dom Pedro II himself, although he failed to guarantee the promised lands.[2]

Today, most of the territory has consolidated its demarcation, after receiving its first official recognition in 1900. In 1931, its boundaries were ratified, but land-tenure problems have never left the descendants of the Guaicurus, as they are also known, in peace. There are countless reports of invasions, land grabbing, and conflicts. In the final demarcation process, which only took place in 1981, the conflict was so intense that a part of the original territory called Xatelodo was left out of the territory’s final perimeter.

In the 1950s, squatters and land grabbers numbered in the thousands and, in the 1980s, increased their numbers even more, encouraged by the Indian Protection Service (SPI) itself. More recent records indicate that by the mid-2000s, more than 100,000 hectares of the official Kadiwéu Indigenous Land had been invaded. Even after the indigenous people occupied land and fought to recover it, at least 80,000 hectares are still under invasion. In other words, the struggle against loggers, leaseholders and ranchers is still under way, and according to the Kadiwéu, the invaders have used a variety of land takeover tactics, such as expanding livestock operations with deforestation and above all, burning.

Notes

Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). Terra Indígena Kadiwéu. In: Terras Indígenas no Brasil.

Caio de Freitas Paes. A história e o mito dos índios cavaleiros do Pantanal, ‘decisive’ in the Paraguay War. BBC News Brasil, December 07, 2019.

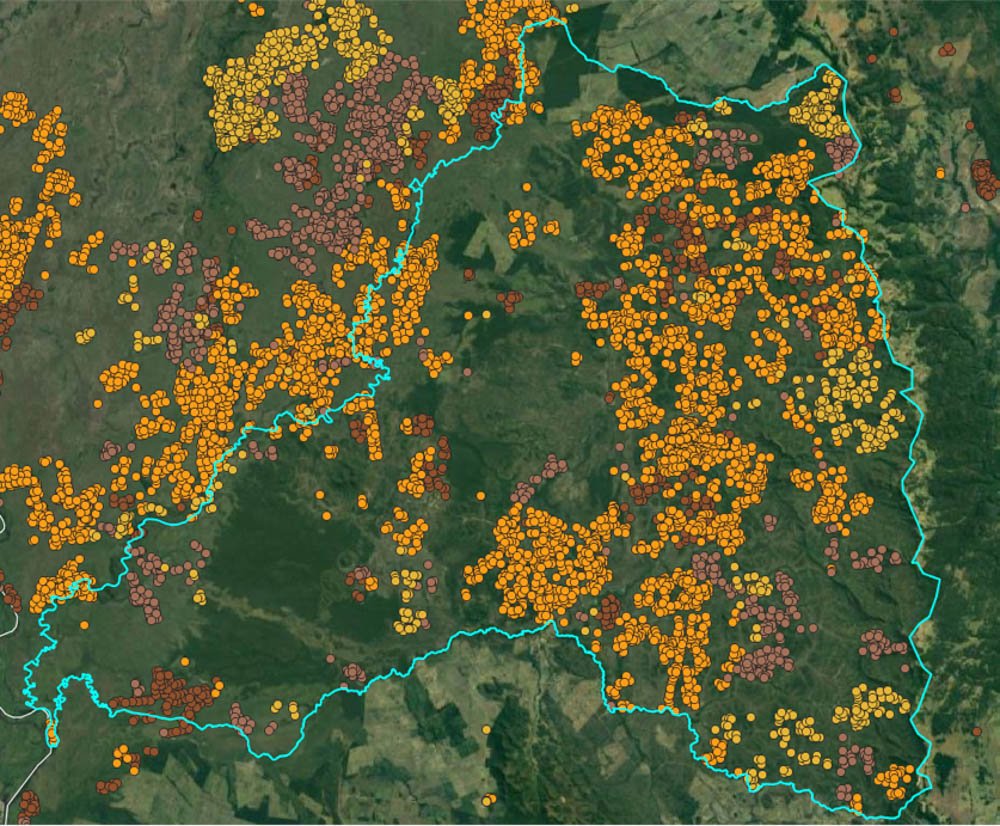

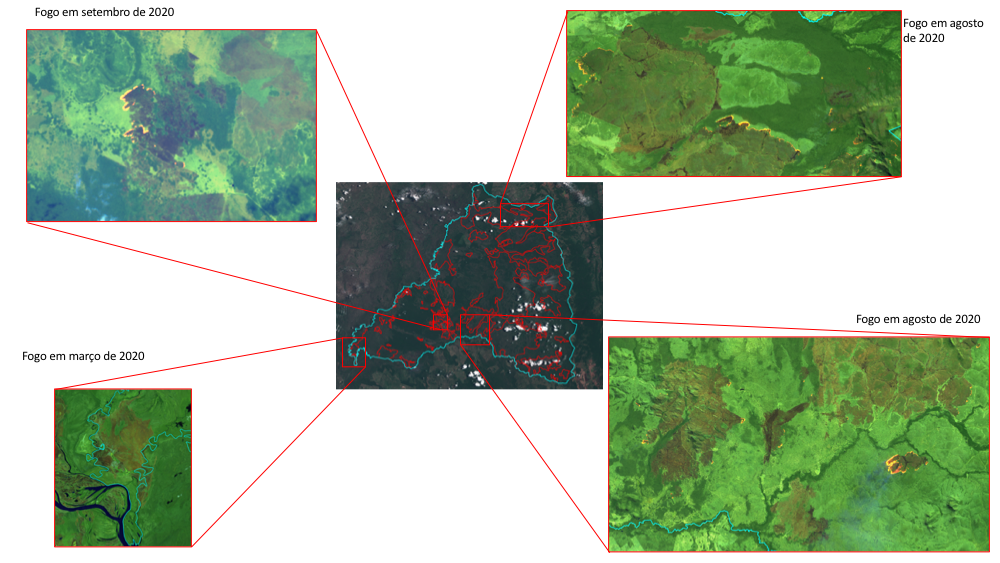

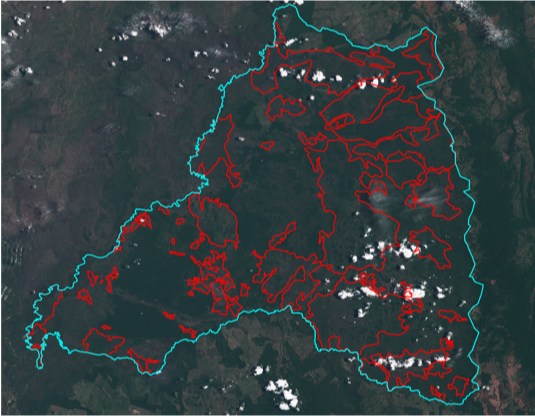

The fires in the Pantanal are rapidly increasing. Four million hectares have already been consumed, 2.9 million of which in 2020 and 1.165 million in MS alone. That area, representing 21% of the total biome (according to the criteria of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics – IBGE), amounts to 20 times the size of the city of São Paulo.[3] Besides the hills, parks and Permanent Preservation Areas, the fires also affected riverine communities and, in an especially tragic manner, indigenous lands located in the region of the municipalities of Corumbá, Porto Murtinho, Miranda and Aquidauana. The indigenous territory most severely affected was the Kadiwéu Indigenous Land.

The damage is nothing new. In 2019 – which had already seen an 88% increase in fire outbreaks in Brazil’s Indigenous Lands – the Kadiwéu Indigenous Land was the second most affected, with more than 613 outbreaks.[4]

Notes

Duda Menegassi. Fogo já atingiu mais de um quinto de todo Pantanal. O Eco, September 24, 2020.

Renato Santana and Tiago Miotto. Focos de incêndio em terras indígenas aumentaram 88% em 2019. CIMI, September 10, 2019.

The surreal, constant and still growing impact was that more than 211,000 hectares burned between March and November 2020 alone, which corresponds to 39.15% of the territory.

It is common knowledge that the fires destroying the Kadiwéu Indigenous Land and other lands and peoples in Mato Grosso do Sul are mostly criminal and intentional. A few months ago, the state government published the findings of Operation Focus, which inspected and investigated criminal fires in the Pantanal wetlands. From the fines alone, about R$ 35 million were collected. Forty ranches were inspected, 19 of which had active fires, and three people were arrested in the act of setting fire to the vegetation cover.[5]

The fires running up and down the Paraguay River basin have left a burning scar in nature. But it is impossible to measure the scale of the cultural and territorial scars that will remain for the state’s indigenous communities, especially the Kadiwéu, if the situation is not urgently contained.

Notes

Karina Campos. Multas por crimes ambientais no Pantanal já somam R$ 35 milhões na Operação Focus. Midiamax, October 15, 2020.

Matias Benno Rempel works with the Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples (Conselho Indigenista Missionário/CIMI) in Mato Grosso do Sul