Mato grosso

Cerrado

But we don’t live to make money.

So the Xavante people need to preserve the Cerrado, right?

Tserebdzaiwe Morodzawe[1]

The people Xavante call themselves in their mother tongue A’uwe, meaning people, or A’uwe Uptabi, meaning real people. They live nowadays in the region of the Serra do Roncador, in eastern Mato Grosso state, in the Indigenous Lands (ILs) Areões, Areões I, Areões II, Chão Preto, Marãiwatsédé, Marechal Rondon, Pimentel Barbosa, Parabubure, Sangradouro/Volta Grande, São Marcos, Ubawawe, and Wedezé. The indigenous people are distributed over patches of a territory they traditionally occupied for at least 180 years[2]. Today, only Chão Preto, Ubawawe and Parabubure are geographically contiguous and, of all the twelve ILs, nine have been officially registered, through procedures completed in 2001[3]. Areões I and Areões II are still in the identification stage and Wedezé has already been identified, but these cases have been on hold since 2011[4].

The expansion of agribusiness started in the 1930s, with the “March westward”, causing migratory and expropriation processes that led to the fragmentation of the Xavante territory into islands. The military dictatorship’s “national economic development” agenda came later to spread large-scale monoculture crops (such as soy, rice, and corn) and, with them, roads for transportation and hydropower dams to generate energy. At the time, violent expulsions with bombings were also one of the Brazilian State’s strategies[5]. The Xavantes only retook parts of their territory after much struggle and visits by their chiefs to Brasilia in the 1970s and 1980s[6].

Before living in the Mato Grosso Cerrado, studies have found it is possible that the Xavantes lived together with the Xerente people, self-designated Akwe, in what is now the state of Tocantins. The two groups form the Acuen ethnolinguistic group and make up the central branch of Jê speaking peoples[7].

Notes

Interview on April 7, 2022, at the “Terra Livre” Camp, in Brasília.

The article in the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (PIB) platform by the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA) about the Xavantes is an important source on the history of these peoples’ relationship with the State and national society, and on the constitution of their sociobiodiversity. Available here. Accessed on March 5, 2022.

The municipalities in which the Xavante ILs are located are: Nova Nazaré, Campinápolis, Alto Boa Vista, São Félix do Araguaia, Bom Jesus do Araguaia, Paranatinga, Nova Xavantina, Água Boa, Canarana, Ribeirão Cascalheira, General Carneiro, Novo São Joaquim, Poxoréu, Barra do Garça, Santo Antônio do Leste and Cocalinho.

For more details, see the biography of Carolina Rewaptu, which narrates the expulsion of the Xavantes from where the Marãiwatsédé IL is today and about the resistance to retake the territory. Available here. Accessed on April 27, 2022.

The reoccupation of IL Marãiwatsédé, after its return by the Italian company, Agip do Brasil S/A, which administered the Suiá-Missú Ranch, one of the largest properties in Brazil at the time, is emblematic of the Xavante resistance, which mobilized nationwide and internationally to put pressure on the company. To learn more about this and other cases, see the following articles: here and here. Accessed on April 26, 2022.

Some theses on the division of the group at the end of the 19th century argue that it occurred while the Xerentes and the Xavantes were resisting the colonial government’s attempts to exploit the Araguaia River, set up villages and “populate” the central-western region of the country. To learn more, see ISA’s article on the Xerentes, available here. Accessed on April 26, 2022.

The Xavantes’ lives and hearts beat with the Cerrado

The Cerrado is the core of Xavante culture and social organization. While it is treated by the State as a mere object to be used by humans and exploited by big companies in the name of “national development”, for the Xavantes, and other indigenous peoples, the Cerrado has another essence: it is an active force that makes the Xavante way of life, way of thinking, and culture possible. Berenice Redzani Toptiro, from the Sangradouro/Volta Grande IL, is a professor studying Intercultural Education at the University of Goiás (UFG). She told us how the Cerrado, in fact, is the central player in the whole Xavante worldview, giving it life, offering everything that nourishes the Xavante body and soul. Yams, pequi (Caryocar brasiliense), Xavante beans, jaguars, bush pigs, moriche palm straw and logs, the waters, and the mountains are some of the ingredients generated by the Cerrado that guarantee the food sovereignty of these many peoples and communities.

Nourishment from the Cerrado relates not only to food, but also to the spiritual world. The rituals and ceremonies of the Xavantes, for example, rely on these fruits, roots, trees, and animals that the Cerrado offers them, and the Xavantes in return care for this land. They must take care of it, because the Cerrado also harbors the souls of its guardians, their ancestors, those who came before and made it possible for today’s people to continue there: “This soul is connected to the Cerrado and nature. It strengthens our minds, and we breathe it every day in the pure air,” Berenice stresses.

It is easy to understand, then, why the Xavante people are known as warriors and remain in the Cerrado to this day, however fragmented they have become after a long history of struggle against invaders[8]. The Xavante live in Mato Grosso, topping the list of states that deforest the Cerrado’s sociobiodiversity[9] and boasting the highest growth rate in agricultural and cattle production for four consecutive years (2018-2021)[10]. Besides that, the Xavantes resist the pressures from ranchers and invaders and pursue alternatives through denunciations and national and international networks, the organization of the Xavantes’ own associations and networks, the creation of indigenous fire brigades[11], and seed fairs, among other initiatives. These have been their strategies to resist the advance in recent decades of waradzu – white people, in their mother tongue – ways of thinking and living.

Fires from Cerrado and arson in Cerrado

Every year, the dry season – from April to October – is critical for the sociobiodiversity in Brazil’s Cerrado because of the ease with which hotspots can ignite and turn into large wildfires. Traditional communities and indigenous peoples, holders of ancestral knowledge to care for and manage the Cerrado, have been organizing for decades, with or without the State, to contain fires that break out during this period, by means, for example, of brigades and the controlled use of fire. These natural conditions of the Cerrado are viewed with respect and care by the Xavantes, who help to contain fires in their territory because they know that without the Cerrado there is no food, no life.

Almost three decades after the first demarcations, ranchers, loggers, entrepreneurs and politicians in the region continue invading and exploiting ILs and trying to co-opt the indigenous people – directly or indirectly[12]. Since 2019, with what became known as the “Day of Fire” on August 10, the situation has become increasingly critical and criminal fires are now a constant reality during the drought. Ranchers and invaders use fire in a criminal way, interested in expanding their production and driving out and weakening traditional communities and peoples.

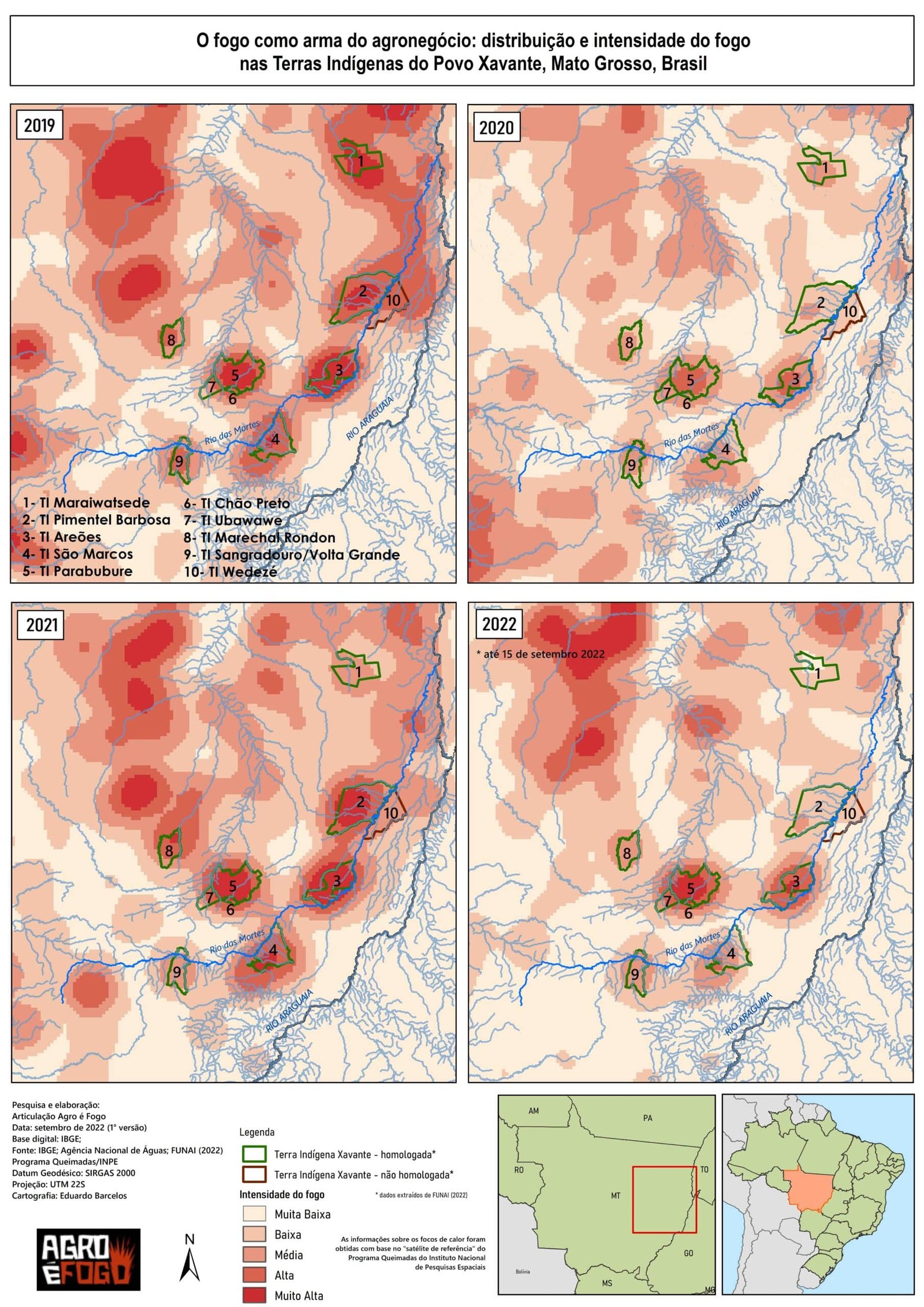

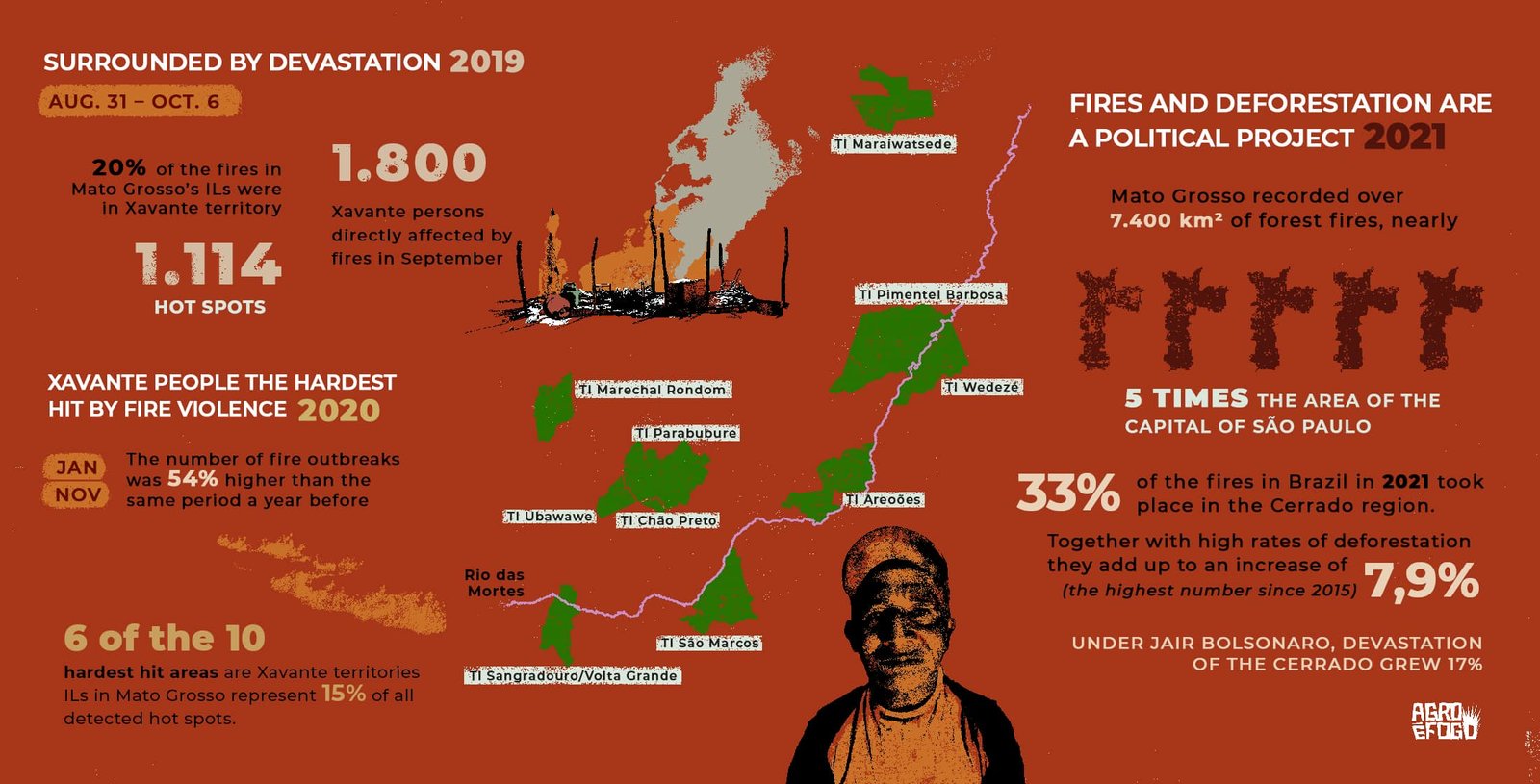

In the period from August 31 to October 6, 2019, 20% of fires in Indigenous Lands in the entire state of Mato Grosso were in Xavante territory (1,114 hot spots). The Areões IL ranked first on the list, followed by São Marcos and Parabubure. Fires are often used to consolidate some deforestation and to make it look like the land is being used.

Operation Siriema, led by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Resources (Ibama) and the Federal Police (PF), was organized to contain those fires, and to identify the arsonists[13]. According to the Xavante Warã Association’s Technical Note 01/2019, “an estimated 1,800 Xavantes were directly affected by the fires in September. … According to reports by our relatives there were situations in which entire villages and fields were burned and residents lost all their material possessions and subsistence agricultural crops.”[14]

The 2020 fire data did not change the upward trend. According to a report by the Center for Life Institute (ICV), the number of fires from January to November was 54% higher than the same period a year before. The state’s ILs accounted for 15% of the total area of fires, and 6 of the 10 most affected areas are Xavante territories[15]. The state government instituted a burning ban period from July 1 to November 12, but it was not enough to keep 2020 from being the worst year for fires in the state since 2007. The Cerrado in Mato Grosso lost 9% of its plant cover to fires. The value of all the sociobiodiversity destroyed by agribusiness for decades is considered high.

2021 was no different. The state of Mato Grosso reported more than 7,400 km2 affected by forest fires (equivalent to five times the area of São Paulo). 33% of these fires were in the Cerrado, which also suffered from high rates of deforestation – 7.9% more than in 2020, according to official federal figures released in the dead of the night, on December 31. That rate was the highest since 2015 and, during the first three years of Jair Bolsonaro’s government, the devastation of the Cerrado had already increased by 17%[17].

According to Tseredawa Morodzawe, the Xavantes manage fire based on traditional knowledge, for both hunting and farming. Landowners and rancher politicians (“ruralistas”) often use this as an argument to justify setting fires on the fringes of the ILs. However, he explains that the Xavante use of fire has another intention: to prepare and nourish the soil for planting. After the indigenous persons, in families or groups, open a specific plot of land to be planted, they wait for the dry season and use fire to burn only that area. Then they let the ashes from the cleared organic matter nourish the soil, which is then cleared and, in the rainy season, sown with seeds[18].

In addition to the crops, which need fire during the cleaning and preparation stage, the Xavantes also use fire control techniques passed on from generation to generation to burn specific enclosures for collective hunting practices. This technical, ancestral knowledge is also under threat. The Xavante people’s use of fire has never threatened sociobiodiversity in the way modern fires set by ranchers and invaders do; on the contrary, it is an important element in their management of the Cerrado.

Notes

To learn more about the history of invasions of Xavante lands and the struggle of this people to ratify and hold on to their territory, access the special report on the Marãiwatsédé Indigenous Land here. Accessed on April 10, 2022.

Mato Grosso as a state ranked 5th among the states that deforested the Cerrado the most from August 2020 to July 2021 (the 2021 deforestation rate), with a total of 803 km2 cleared, 4% more than the year before. Source. Accessed on April 27, 2022.

To learn more about the various brigades working to contain fires throughout Mato Grosso, see the platform set up by ICV in 2021.

Parabubure, Pimentel Barbosa, Areões, São Marcos, Sangradouro/Volta Grande and Marãiwatsédé. Available here. Accessed on April 25, 2022.

This number refers to the period from January 1 to July 13, 2021. In other words, the dry season (second semester), considered the most critical for the region, had not even begun, and the fire figures were already alarming. Available here. Accessed on April 26, 2022.

The Covid-19 pandemic since 2020 has aggravated the situation even more. Environmental inspections by Ibama and the Federal Police, and support from the National Indian Foundation (Funai) became less frequent, leading to a considerable increase in areas affected by arson and invasions in the ILs, especially those close to highways, as is the case of Sangradouro/Volta Grande[19]. Many elders have died from contagious infections, due to poor controls over the movement of people into and out of the territories.

Another serious problem in this period was the intensification of violence in relations between white and indigenous people. As the pandemic reduced all the support and supervision provided to ILs by state and federal authorities – which had already become increasingly deficient in the last five years – this period was also perceived as an opportunity by landowners, ranchers, entrepreneurs, and politicians in the region to coerce, threaten, and blackmail indigenous people, especially whenever they questioned the presence of those forces in their territory.

Fire is one of the threats they use, as many ranchers take advantage of periods of collective hunting or the opening of fields to burn nearby areas and then criminalize and blame the indigenous people. This is also a public health problem. In the past, the average number of cases of indigenous people with respiratory ailments cared for was between 10 and 70 per month, but beginning in 2019, that figure jumped to 1,500 in some months, as reported by the Xavante Indigenous Health District Coordinator, Luciene Cândida Gomes. This increase also coincides with more fires and the advance of agribusiness into their territories.

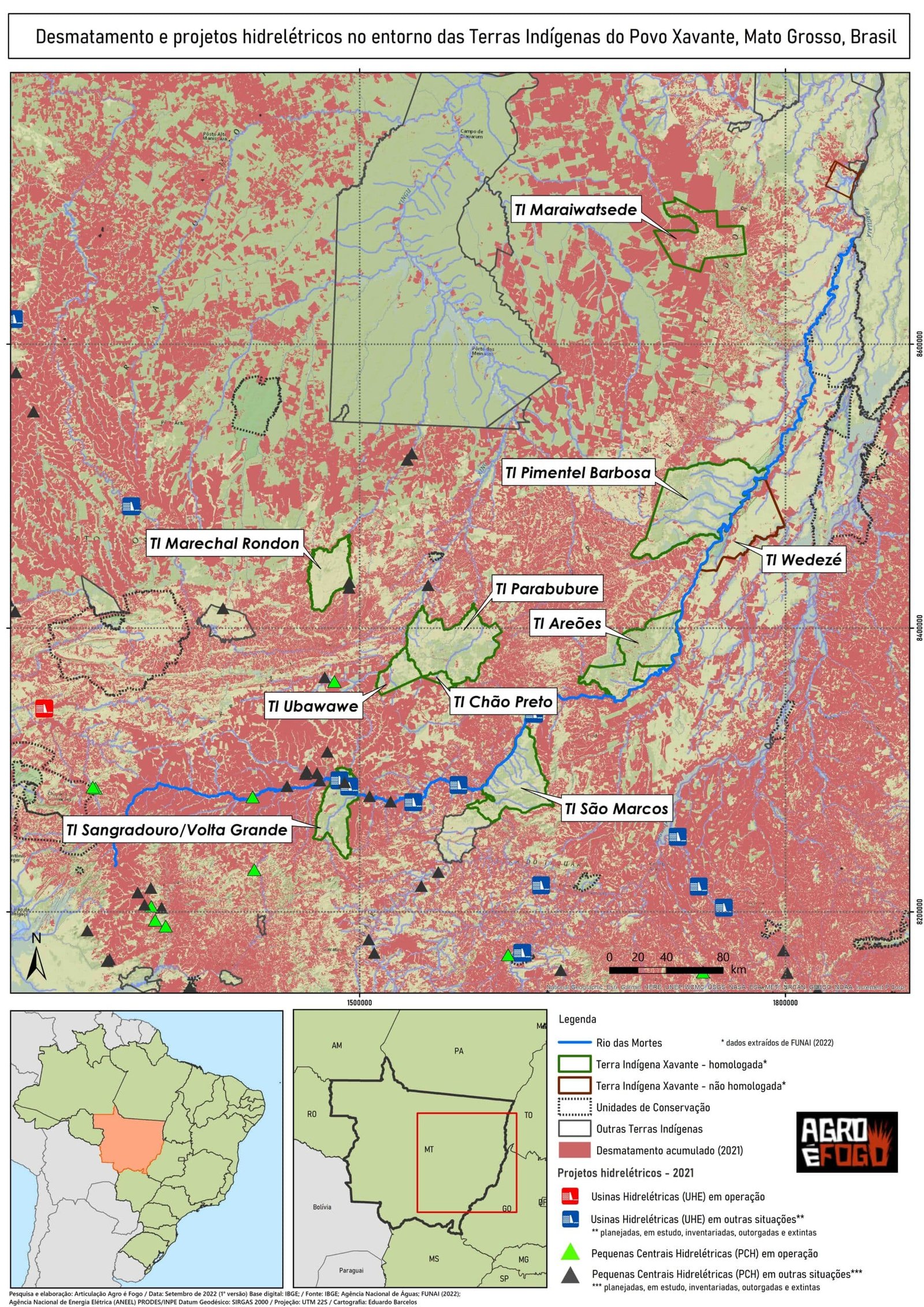

Deforestation, threats and divisions

Of the ten most deforested protected areas from August 2020 to July 2021 in Mato Grosso, six belong to the Xavante people, led by the Sangradouro/Volta Grande IL, where part of the land was used for mechanized rice plantations through a “partnership” between some indigenous persons, the Primavera do Leste Rural (Landowners’) Union, the state government, and Funai, as part of the AgroXavante Project[20] or Indigenous Independence Project, in December 2020. In May 2021, 24 indigenous people were working at the site and 50 hectares were already set aside for crops. The forecast at the time was to expand to 1,000 hectares by the end of 2021[21].

This project was conceived to promote political interests of the region’s landowners, local agribusiness politicians and congressmen, fostered by the Bolsonaro government. In March 2022, in a promotional video published on his social network, state assembly member Xuxu Dal Molin (PSC), together with federal congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro (PL-SP), praised the actions of AgroXavante in Sangradouro/Volta Grande and defined the Cerrado as “green gold”, a region that “has no forest to manage”, but that can produce “food” for the Brazilian population, while giving “economic independence” to indigenous people[23]. The video makes direct reference to the support of President Jair Bolsonaro and of the president of Funai at the time, Federal Police official Marcelo Xavier[24].

The project is unconstitutional, for it is based on a minority of the indigenous population and has provoked several conflicts. All the indigenous persons interviewed for this case study were adamant in asserting that the leasing of their lands to agribusiness, through AgroXavante, or any other unconstitutional initiative, is destructive to the Cerrado and to Xavante life itself. It has been identified by most Xavantes, not only those in the Sangradouro/Volta Grande IL, as a means of generating conflicts, divisions, and clashes among members of their own people[25].

Warã Xavante Association[26]

The Xavantes have been facing a serious food security crisis, which they have identified as one of the main reasons why some of their members have joined the project. Fires and deforestation kill plants, roots, and animals, in addition to scaring off prey, all of them essential for food. And even with no official authorization or legal consultations, what the Xavantes have experienced on at least 50% of their officially registered indigenous land is an increase in the number of pastures along the boundaries, for cattle to be sold on the external market.

In addition, the Xavante people face the harmful effects of pesticides and other chemicals used abundantly on monoculture plantations around their territory, contaminating the water, soil, and air, poisoning their crops and livestock. These environmental crimes contribute greatly to increasing the Xavante’s food insecurity and their subsequent dependence on money to buy food from stores in the city.

The secretary of the Xavante Warã Association, Noberto Tseredawa, from the Parabubure IL, underlines how projects like AgroXavante are aimed only at weakening his people and decreasing their nutritional resources. In his village, some of the indigenous persons are inclined to accept it, but, according to Tseredawa, they are misinformed about direct and indirect impacts of this type of project. Jurandir Siridewê, from the Pimentel Barbosa IL, also commented on how hard it is to dialogue with landowners after Bolsonaro’s election: the tone of relationships changed and has become more violent, and deforestation is no longer seen as an illegal practice, since the president himself encourages it[27].

In the Marãiwatsedé IL, the involvement of the Funai’s regional coordinator for Ribeirão Cascalheiras and two police officers in the illegal use of Xavante community resources was recently made public[28]. The Federal Police’s Operation Res Capta (Latin for “thing taken”), in March 2022, investigated the illegal leasing of IL areas to “landowners”, directed by the Funai coordinator with the support of two other police officers. The three officials were indicted for passive corruption and deforestation of public areas. The dismantling and militarization of FUNAI staff positions since 2019 have contributed to an intensification of invasions, since the agency, instead of fulfilling its enforcement role, has been mediating and enabling the enrichment of public servants at the expense of Xavantes and other indigenous peoples.

This case gained in complexity when it was confirmed that tribal chief Damião Paridzané was also involved in the leases. Damião has not denied the accusation, but his defense claims the money was distributed among all the communities of the IL and that the leasing was a survival strategy in response to the growing number of invasions and the impossibility of subsisting solely on the socio-biodiversity of their territory[29]. The note from the Indigenist Missionary Council (Cimi)[30] on this case also reinforces the understanding that, in the current scenario of total invisibility of the demands and needs of the indigenous people, situations like this can only be reversed if authorities actually strive to recover degraded areas, constantly supervise the ILs, and guarantee that the Xavante territory is not only the place where they live, but also the foundation for producing and reproducing their livelihoods and culture.

Other forms of Xavante resistance

In addition to the threats of fire, deforestation, and land grabbing, there is also a proposal under way since 2012 to install Small Hydropower Plants (PCHs) along the course of the Mortes River – called ö wawe, or “big water”, in the native language – a tributary of the Araguaia River. The river flows through 33% of the territory (the Areões, Pimentel Barbosa, Sangradouro/Volta Grande and São Marcos ILs), but only the Sangradouro IL is being considered in the process. Three projects belong to the Bom Futuro Energia company: the Cumbuco PCH, the Geóloga Lucimar Gomes PCH, and the Entre Rios PCH.

These projects are direct threats to food security, by decreasing the availability of fish and altering the conditions of the river’s headwaters. Indirectly, these projects can also further weaken and divide the Xavantes and co-opt some of them into the waradzu model.

Notes

In a report by Rubens Valente, we learn that the project has been going on since 2017 and that, upon taking office, President Bolsonaro began to act, along with the then Minister of the Environment, Ricardo Salles, with the Minister of Agriculture, Tereza Cristina, and with the Minister of the Federal Court of Accounts, to implement it. See more here. Accessed on April 28, 2022.

For further details, listen to Ep 12 – Independência Indígena do podcast Marimbá. Available here. Accessed on April 16, 2022.

The judge in the case even authorized use of the funds because she found that the Marãiwatsedé indigenous people have had to obtain their daily sustenance not from the Cerrado, but from local stores, because the socio-biodiversity of their territory is threatened by past and recent degradation. Available here. Accessed on June 2, 2022.

In March 2020, chiefs, leaders and associations of these ILs released a note questioning the company[31]. According to the document, the process is illegitimate – for not following international protocols and excluding Xavante ILs that will be impacted – and criminal – for working to divide the people, harassing some of the indigenous people to submit and excluding those who do not. The fact that the concessions do not follow International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 169[32] consultation procedures is always stressed.

To guarantee their rights, some of the Xavantes have mobilized other indigenous persons to attend public hearings, to increase pressure and also to learn more about these projects. Education, knowledge sharing, and political mobilization are the Xavante’s strategies to resist the misinformation and the division generated by these projects.

That firm resistance, indeed, is very evident in the opposition organized by the Xavantes themselves, both in their technical and protest statements, widely disseminated by institutions such as the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA) and Cimi, and in their constant learning process about new avenues of resistance.

Today, the Xavante associations and networks have adopted digital communication tools and receive help from journalists to publicize attacks against them and to give visibility to the reality of the Xavantes in the Cerrado. In the last week of April 2022, Berenice and other Xavante indigenous persons participated in a workshop on ethno-communication in the Sangradouro IL, expanding their strategies to avoid the co-optation of more indigenous persons and to increase the knowledge of non-indigenous people about the Xavante people’s worldview, which must be respected and valued.

All this knowledge about their rights comes from a long history of generations who resist, denounce, seek support inside and outside the country and, of course, keep teaching the younger ones.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), in another expression of this resistance, is investigating a complaint about impacts of the expansion of the BR-080 highway, pushed by the Bolsonaro government as a form of development, which will pass 16 km from the area that is home to the oldest Xavante village in the region, the Sõrepré. This village, considered the last of the period before the diaspora which began after contact with the waradzu, has a special spiritual and archeological importance, according to the indigenous people themselves as well as outside researchers. There are remnants of the sacred territory on the Campo Alto Farm, which does not recognize its existence and has not cooperated with the research. The Xavantes sought clarification on the lack of prior consultation and took the complaint to the UN, generating recommendations from the UN Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. So far, since neither the recommendations nor the indigenous people have been heeded by the government, the MPF has been brought into action[33].

Ana Carolina Oliveira is a researcher, with a degree in Anthropology from the University of Brasilia, and experience in issues related to socio-environmental policies in Brazil, large corporations, and the lives of traditional and original peoples. She also works with studies on international cooperation for development.

Hiparidi Dzutsi’wa Toptiro is the General Coordinator of MOPIC (Mobilization of the Indigenous Peoples of the Cerrado), Political Advisor to the Xavante Warã Association and chief of the Abelhinha village in the Sangradouro IL.

We thank the Xavante Warã Association for their support in writing this case study and also Berenice Redzani Toptiro, Félix Tsiwetsudu Tseredze, Noberto Tseredawa, Tserebdzaiwe Morodzawe and Rivelino Adzowe for their contributions with interviews and conversations.