Mato Grosso do Sul State

PANTANAL REGION

In 2020, the Pantanal, the largest continuous wetlands in the world, was prominently featured in the news when large forest fires swept through the region, destroying almost a third of its total area. In the state of Mato Grosso do Sul alone, 1.7 million hectares turned to ashes. According to the Pantanal Observatory organization [Observatório do Pantanal], approximately 4.6 billion animals were affected and at least 10 million died as a result of the fires.[1] It is already known that both in Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul states, the fire originated in cattle farms before it spread throughout the territory.[2]

Forest fires in the Brazilian Pantanal had already been wreaking havoc prior to 2020, as recalled by Dona Leonida Aires, a resident of the Barra de São Lourenço traditional pantaneira community, and president of the Renascer association of women artisans:

Notes

See: “Um ano após perder 26% do bioma, Pantanal corre o risco de ter incêndios piores neste inverno” [“One year after losing 26% of its biome, Pantanal at risk of more aggressive fires this winter”], from G1. 07/10/2021.

See another article from this same dossier, titled “Fire in the Pantanal:

the home of its traditional communities is burning”.

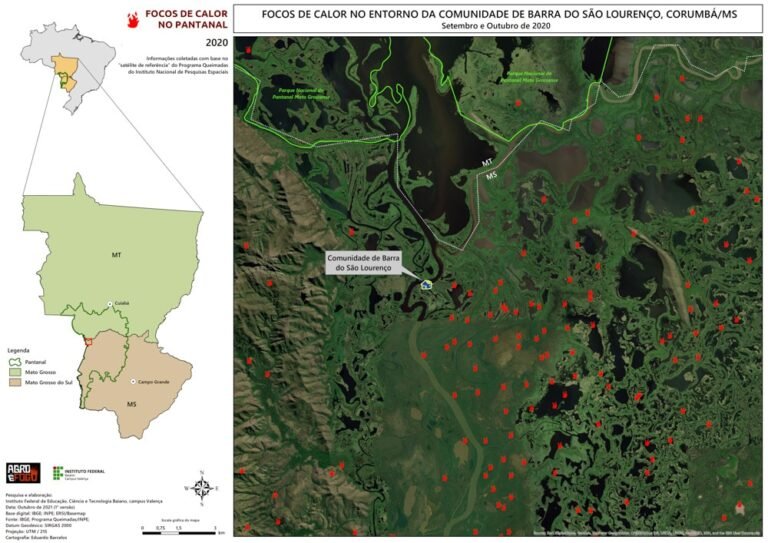

The Barra de São Lourenço traditional pantaneira community is located in the municipality of Corumbá, state of Mato Grosso do Sul. It is situated in a permanently flooded area, near the international border between Brazil and Bolivia, just beneath the confluence with the Cuiabá river, on an island on the left bank of the Paraguay river. The community covers an area of 12,241 square meters and was declared an area of public interest by the Federal Heritage Office (Secretaria do Patrimônio da União, SPU), as per ordinance no. 57 of April 2016. Currently, Barra de São Lourenço community is fighting for its territory to be recognized as a Sustainable Development Reserve (Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável, RDS).

The community is home to 25 families, a number that was much higher in previous decades. Their livelihood revolves around traditional fishing practices, gathering live bait, producing native rice crops, extracting aguapé (Eicchornia crassipes) for use in making handicrafts, harvesting fruits and other natural resources, in addition to small-scale farming and livestock ranching. They utilize, manage, and conserve the Pantanal territory by employing complex knowledge systems and practices that ensure abundance for future generations.

The region where the community is located is one of the better preserved areas of the Pantanal, comprising several protected areas, such as the Private Reserve of Cultural Heritage (Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Cultural, RPPN), and the Pantanal National Park [Parque Nacional do Pantanal], which are manaced by the harmful actions taking place in the upper Pantanal region, such as deforestation, pesticide use, and the silting of water resources.

In this region, known as Amolar, the fires were most intense between September and October of 2020, and reached the banks of the Paraguay river, located 223 km from the municipality’s headquarters and about 8 hours by boat north of Corumbá. Remembered by the community as “days of fire”, of Dona Leonida recalled that:

In previous years, the fire reached nearby areas but not the community’s territory. Community residents teamed up by setting up a volunteer firefighting brigade that often fought the fires in the region, based on traditional knowledge derived from their deep attachments to ancestral territory.

The fires that hit the community in 2020 and 2021 originated in nearby areas, such as the Pantanal National Park and local agribusiness farms, as established by the federal police in an ongoing restricted investigation.

After the fire, came the ash fallout

Engulfed by these incidents, the community did not anticipate what was to come next: the ash fallout that enveloped their territory following a climatic phenomenon. It was October 13, 2020, and as per Dona Leonida:

Well, then the fire was put out, and all our agony came to an end. Until then, we were, as they say, feeling like we were above the fire. That we were being burned alive because it was so close. But by the grace of God it was over. At least we thought it was over, because then the rain came. We were very happy, despite everything being scorched, destroyed… But unfortunately the ordeal wasn’t over.

Suddenly, there was a windstorm, and the wind gave rise to a huge black blur that we couldn’t identify. I couldn’t explain what it was. At once, it began moving closer and closer… Then we realized it was not smoke, and we thought: by God, fire again? Is it burning again? But it wasn’t fire, it was ash, a great deal of it, ash coming down so hard… We covered our doors and threw water on our faces before putting on our masks, you know? Because that’s what we used to do when the fire was burning, we wet our masks before putting them on so we could breathe. Then we would dip a towel in water and throw it over our heads like this, you know? So we could breathe and protect our heads. With the children it was more difficult because they did not want to have their faces covered, as soon as you put their masks on, they wanted to take them off.

As this report shows, the situation faced by this and other traditional pantaneira communities is dire. From 2020 to 2021, there was not enough rain to replenish and “wash off” the Pantanal. As a result, water from rivers and streams, bays and streamlets, is scarce. Water levels are low, some sources are drying, and hence muddy, intermixed with ashes from the fires. This scenario denotes the fragility of the ecosystem and how it affects those who live in and share it.

The Barra de São Lourenço community continues to face many challenges, especially those related to water quality and scarcity.

The community carries out several initiatives that highlight its spirit of hope and resistance, such as the maintenance of a communal vegetable garden, collection of fruits for seedling production, and implementation of a native seedling nursery that will pave the way for the environmental and ecological restoration of the territory. In order to better prepare for the fires, the community has been bolstering its volunteer fire brigade, with its members partaking in fire-fighting trainings and opening a communication channel that will link them with potential partnerships and projects. They remain expectant that their collective rights as a traditional pantaneira community will be recognized and enforced in all corners of the Pantanal.

It is imperative that the State take action by investigating and exposing those responsible for the environmental crimes that have caused irreparable damage to the Pantanal region. Answering these challenges will encompass advocating for public policies and recognizing that, in direct opposition to the devastating fires caused by agribusiness, lie the community’s[3] traditional fire management practices.

Notas

On the traditional use of fire by communities, see “Saberes que vem de longe: usos tradicionais do fogo no Cerrado e na Amazônia” [“Knowledge from afar: traditional fire use in the Cerrado and Amazon“]

Cláudia Sala de Pinho is a regional coordinator at the Pantaneira Network of Traditional Communities [Rede de Comunidades Tradicionais Pantaneira] and former president and advisor to the National Council of Traditional Peoples and Communities (Conselho Nacional de Povos e Comunidades Tradicionais, CNPCT)