THE EXPANSION OF MINING ON INDIGENOUS LANDS: An enemy with hooves of iron and gold

By Luis Ventura Fernández – CIMI Norte I

“We Yanomami have other riches left by our ancestors that white people cannot see: the land that gives us life, the clean water we drink, our happy children.Do you white people think that we are birds, or that we are rodents, to give us only the right to eat the fruit that sprout from our lands? We don’t think of things as separate, we think of our land-forest as a whole. If you destroy what is below the ground, everything above will also suffer.”

Davi K. Yanomami

Mining within indigenous territories is not regulated and, therefore, is an illegal activity. In recent decades, economic sectors and public authorities have attempted in various ways to open these territories to mineral exploitation. These advances are met with firm resistance from indigenous peoples. Since January 2019, the Jair Bolsonaro administration has amplified this offensive, resulting in the expansion of mining and in an increase in applications for mineral research and mining.

Bolsonaro’s political project is clear and explicit in its intentions. It involves de-constitutionalizing the collective rights of indigenous peoples and deterritorializing the areas they occupy, using an integrationist and racist rhetoric against the autonomy of those peoples. To this end, it is following to the letter its promise not to demarcate any indigenous land, in violation of the 1988 Federal Constitution, which mandates the Federal Government to implement the demarcation and protection of territories.

According to the Indigenist Missionary Council (Conselho Indigenista Missionário, Cimi) report “Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil”[1], in 2020, a total of 832 indigenous lands were still pending administrative demarcation and registration procedures. However, in April 2020 then Minister of Justice Sérgio Moro, complying with the deceptive premise of the Marco Temporal (“Time Limit Trick”)[2], still sent 17 indigenous territories that were already in an advanced stage of delimitation and demarcation to the initial stage of the administrative procedure.[3]

The deterritorialization process proposed by the current administration also includes the opening up of indigenous territories – demarcated or not – to agribusiness and mining capital. The intention is the accelerated and extensive exploitation of natural assets to intensify the export pattern of the Brazilian economy, while satisfying the interests of the economic sectors that sustain the Bolsonaro administration itself.

In order to be able to fulfill this extermination project, Bolsonaro had to rig the National Indian Foundation (Fundação Nacional do Índio, FUNAI), whose institutional mission is to protect the rights of indigenous peoples, to place it at the service of the private interests of farmers, agribusinessmen, gold miners and mining companies. FUNAI now considers that the indigenous peoples who claim their territorial rights in areas not yet administratively demarcated are the “invaders”.

The current scenario of mining advances on indigenous territories must be analyzed precisely in this context of intensification and deepening of the dismantling of indigenous peoples’ rights and of indigenous policies.

Notes

CIMI, 2021. Report of Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil. 2020 data.

The Marco Temporal (“Time Limit Trick”) is an interpretation of Article 231 of the Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988, defended by the rural sector and State agents, according to which, indigenous peoples would only have the right to the lands that they traditionally occupy if they were there on the date of the passing of the Federal Constitution (05/10/1988) or, if they were not occupying the land at that time, if they could demonstrate that there was in fact a possessory conflict or a litigation ongoing in court. This interpretation is clearly unconstitutional and goes against the inherent rights of indigenous peoples to their territories, besides legitimizing the violence practiced against the peoples before 1988, which caused the expropriation of the lands they inhabited.

In Brazil, the administrative procedure for the regularization of an indigenous land has been legally defined since 1996 and foresees 05 stages, which range from the identification of the territory claimed by the communities (from a historical, anthropological, geographical point of view), to the delimitation and physical demarcation (with identification plates of the limits), until the formal registry as public land of the State ceded in permanent usufruct of the indigenous peoples. This complex procedure can take months or years, depending on the particular and economic interests that other actors have over the same territory and on the political will of the Public Power at any given time.

Indigenous peoples' inherent right to their territories: the main bridle to stop mining expansionism

The Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988 recognizes the inherent right of indigenous peoples to their territories and guarantees their right to exclusive usufruct over the natural assets found therein. It sustained the difference between the property of land and underground mineral deposits (CF1988, art. 176). Any action for the exploitation of assets underground will substantially affect the possibilities of usufruct of the assets on the surface.

The Federal Constitution, in the spirit of safeguarding the rights of indigenous peoples, also stated that mineral exploitation within their lands could only take place upon authorization from the National Congress and in consultation with the indigenous communities. In any case, potential mining exploitation on indigenous lands should be regulated by Complementary Legislation.

Furthermore, Convention 169[4] of the International Labour Organization (ILO), ratified by Brazil in 2004, recognizes the right of indigenous peoples to freely determine their own development paths (art. 7) and to be consulted in a prior, free, and informed manner (art. 6), and determines specific procedures related to mineral exploitation (art. 15.2).

Therefore, although considering the State’s ownership of underground assets, both the Federal Constitution of 1988 and ILO Convention 169 state indigenous peoples’ inherent right to their territories and the exclusive usufruct over the natural assets existing therein as substantial and irreplaceable references in considering any initiative of mineral exploitation of these areas.

Indigenous lands are, hence, inalienable, and unavailable, and have no other function than to guarantee indigenous people’s possibility of ruling their own life. These are the rights that should prevail when it comes to resolving any conflicts of interpretation or interest. This is not what in fact happens in Brazil and it is clearly not what guides the Bolsonaro administration’s political agenda.

In January 2020, the Federal Government submitted legislation to Congress, Bill 191/2020, which intends to regulate mining and hydrocarbon exploitation within indigenous lands. The change of speakers of the House and Federal Senate, made possible by old political “give-and-take” tactics with Centrist parties, created a more favorable environment for the agribusiness and mining agendas. Bill 191/2020 on mining on indigenous lands was one of the urgent legislative initiatives that the Federal Government submitted to the new Speaker of the House of Representatives in March 2021. While with the different forces at play at that moment and the irruption of the Covid-19 pandemic the bill’s analysis was suspended in 2020, it seems likely that by the October 2022 elections there will be increasing pressure for its approval by Congress.

The government and congressmen intend to accelerate the passing of such laws[5] this year with the fear that the 2022 election will not guarantee the continuity of this dismantling project. For this reason, initiatives such as Bill 490/2007 – which changes the demarcation of indigenous lands and establishes the Marco Temporal – or Bill 2633 – known as the land-grabbing law –, among others, began to be put on the agenda in the plenary abruptly, quickly, without the necessary dialogue and, sometimes, without going through Congress’ committees or disregarding their opinion. The breakdown of parliamentary dynamics and the rushing to approve controversial initiatives are clear signs of the political intentions established at this moment in Congress. In this context, Bill 191/2020 may be put on the agenda at any time.

Notes

ILO Convention 169. Currently, the Legislative Decree Project n. 177/2021, initiated by congressman Alceu Moreira (MDB Party/Rio Grande do Sul), is circulating in the National Congress, which intends to authorize the President of the Republic to repudiate this Convention.

The Brazilian government used the expression “run the cattle herd” to refer to the policy of destruction of all environmental protection and control measures.

Increase in mining applications on indigenous territories

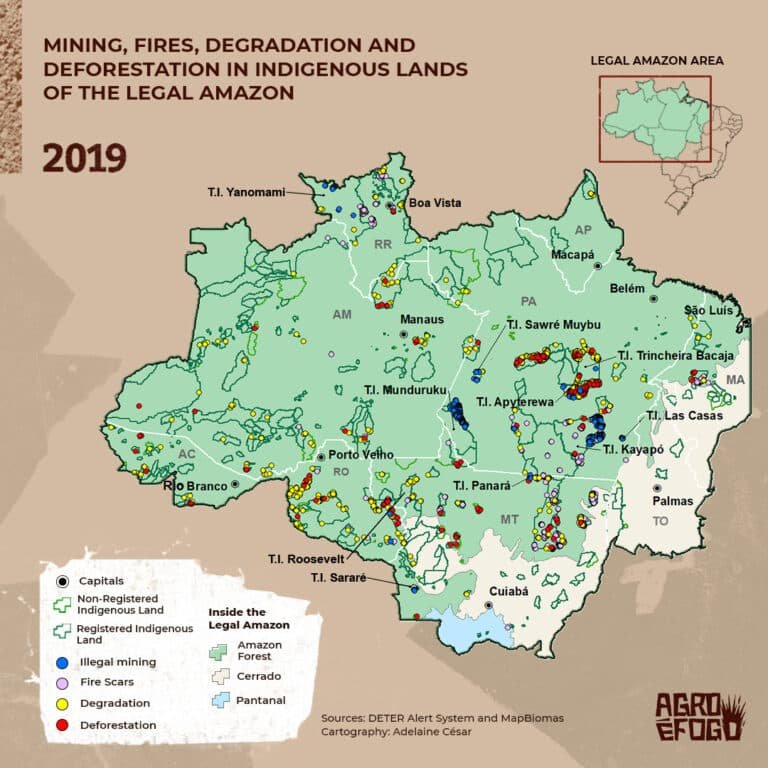

Even though mining is illegal within indigenous lands, in November 2020, the National Mining Agency (Agência Nacional de Mineração, ANM) had more than 3,000 active requests for research or mining within indigenous territories. Among these, 58 applications had already been approved by the ANM[6], establishing a clear illegality. Thirteen of them affected the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Land (Munduruku people), in the mid-Tapajós River region, and granted the Mineral Extraction Cooperative of Vale do Tapajós the right to extract cassiterite until July 2022. In 2020 alone, 145 new requests to be authorized within indigenous lands[7] were filed with the ANM. This is the highest number of applications since 1996.

Between June and August, two Federal Justice decisions accepted the arguments of the Federal Public Prosecution Service of Pará (MPF) forcing the ANM to suspend authorizations for mineral research and mining exploitation in areas incident to the Parakanã (Parakanã people) and Trocara (Assurini people) Indigenous Lands in the Tucuruí region (Pará), and other lands in the Santarém[8] region. Several offices of the MPF in various states of the country filed similar actions requesting the immediate suspension of all authorization requests within indigenous territories.

According to data collected in the Geographic Information System of Mining (SIGMINE)[9], the three periods with the highest number of requests for research and mining within indigenous lands in the last 40 years were: a) 1983-1984, coinciding with Decree 88.895/83 passed by the administration at that time, which intended to regulate mining within indigenous territories; b) 1996, the year in which the Bill 1610/96 was filed in the Senate, the first attempt at regulation after the Federal Constitution; and c) 2020, after the Bolsonaro administration filed Bill 191.

It is clear, therefore, that whenever there is real expectation of regularization of mining on indigenous lands, the market automatically heats up and the number of applications increases significantly, even before regularization takes place.

This is a two-way relationship: the expectation of regulation encourages the mining market and, at the same time, the increase in requests from the market feeds the narrative of “legitimacy and urgency” of the political initiative for regularization.

The illegal mining (garimpo) invasion

Mining does not increase only through the applications in the ANM or the pressure on communities and the National Congress. In recent years there has been a massive increase in illegal mining activity[10] inside indigenous territories in Brazil, particularly in the Amazon, financed by powerful business interests.

On the one hand gold mining activity has been increasing in recent years, in a scenario of greater demand for gold and the rise in its international price. On the other hand, it is evident that gold mining has also found in the current Jair Bolsonaro administration its best narrative, greatest support, and incentive. In areas of difficult access in the Yanomami Indigenous Land or the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Land, for example, gold miners passed on the message to the indigenous people that “everything was now legal, that things had changed and that the best thing the indigenous people could do was to contribute to mining”. The gold miners’ sense of impunity is not a mere delusion, but rather a concrete conclusion, from public statements by the President of the Republic himself or other government authorities.

The government has encouraged and highlighted this perverse cycle of environmental destruction in various ways: from public support for illegal mining activities and land grabbing to the systematic dismantling of policies of enforcement and monitoring in the region. The increase in fires and deforestation in the Amazon since 2019 are part of a systematic and planned project to expand agro-mining capital.

Notes

“Government agency authorizes 58 mining applications in Amazon’s indigenous territories” Amazonia Minada (2020, in Portuguese). Last accessed on August 1, 2021:

“With Bolsonaro’s encouragement, requests to mine on indigenous lands hit record numbers in 2020,” Infoamazonia (2020, in Portuguese). Last accessed on August 1, 2021.

Sistema de Informação Geográfica da Mineração, SIMINE, is an online platform maintained by the National Mining Agency.

The term “garimpo” in Brazil refers to the activity of mineral exploitation of certain substances, in watercourses or on land, with various levels of technological complexity. The mining process is carried out by informal groups or cooperatives of miners, in hierarchical schemes. There is, for example, the figure of the “owner of the garimpo”, who is the illegal owner of the mineral exploitation and of all the extracted products. The garimpo hides corrupt schemes in which big businessmen and politicians participate invisibly. Most of the garimpo in Brazil takes place within indigenous lands and preservation areas, which is absolutely illegal. Here we use the term “illegal mining” or “gold mining” to refer to garimpo due to the predominance of this kind of mineral exploitation.

According to alerts from the deforestation and mining control system (the DETER system), of the National Institute for Space Research (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, INPE), 72% of all illegal mining activities in the Amazon between January and April 2020 occurred within protected areas, such as indigenous lands, environmental preservation areas and conservation units[11]. Within indigenous territories only, the area deforested for mining increased by 13.44% in the same months, and mining activities increased by 64% if compared to the same period in 2019. Between January and August 2021 alone, the area deforested for mining in the Amazon exceeded the total of 2020[12]. In a survey conducted by the Federal University of Minas Gerais together with MPF, between 2019 and 2020 an estimated volume of 100 tons of mercury were used in illegal gold mining in the Amazon[13]. Indigenous leaders are threatened when they report mining within their territories, and no one is held accountable for these crimes.

One of the most evident cases of the expansion of mining is the Yanomami Indigenous Land. The exploitation of mining in the territory where the Yanomami and Ye’kwana peoples live has had a tragic history since the 1970s, when the gold mining incursions increased in number, taking advantage of the opening of roads and the encouragement by public authorities at the time. In the late 1980s, some 40,000 miners were removed, after numerous complaints were filed both nationally and internationally, after leaving terrible stains among the Yanomami people in the form of epidemics (measles, flu, malaria), social impacts, and environmental destruction. In 1993, 16 Yanomamis were murdered by gold miners in what became known as the “Haximu massacre”, the only case to date that has been tried as a crime of genocide by the Brazilian legal system. In the last four years, from 2017 to 2021, the intensity of gold mining within the Yanomami Indigenous Land has reached extreme figures again.

In 2017, there was already evidence of the advance of mining in the Serra da Estrutura region, within the Yanomami Indigenous Land, an area where isolated Moxihatëtëa groups reside. The deactivation of the Ethno-environmental Protection Base in the region, which is under the responsibility of FUNAI, made the incursion and installation of gold mining camps possible. The Federal Public Prosecution Service of Roraima, (MPF/RR), requested in a Public Civil Suit (ACP) that FUNAI reestablish all three Ethno-environmental Protection Bases. This action, granted by the Federal Court in the 1st instance in November 2018, started an intense process of legal measures that has been disregarded until today by the Brazilian State.

Notes

Greenpeace. “Amid Covid, 72% of mining in the Amazon was in ‘protected’ areas” (in Portuguese). Last accessed on August 1, 2021.

According to data from the Real-Time Deforestation Detection System – DETER (INPE), considering a series of data collection since 2015, the level of deforestation in the Amazon due to mining has been increasing exponentially since 2019, coinciding with the beginning of Bolsonaro’s administration, and continues to break records.

“Explosion of illegal gold mining in the Amazon dumps 100 tons of mercury into the region”. El País (2021, in Portuguese). Last accessed on August 1, 2021.

Between 2018 and 2021, indigenous and indigenist organizations have been reporting recurrent cases of violence against Yanomami and Ye’kwana communities by gold miners. The Hutukara Yanomami Association (HAY) states that since 2019 there have been more than 20,000 miners within the Indigenous Land. The spread of the Covid-19 pandemic within the territory has not triggered any territorial protection measures on the part of the Federal Government, and gold mining has become a vector of contagion, an obstacle to the health care of the communities (health teams being removed due to conflicts involving miners) and has even been paramount in a Covid-19 vaccine misconduct scheme in exchange for gold.

From November 2018 to May 2021, five judicial decisions in the Federal Justice system – including the Supreme Federal Court – and precautionary measures from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights – IACHR – mandated the Federal Government to establish, as a matter of urgency, effective actions to confront Covid-19 in the Yanomami Indigenous Land, to control and protect the territory, to reactivate the protection bases, and to remove the miners. So far, the government has only carried out specific and localized operations, with little effectiveness and transparency, without forming a commitment of political standing to confront the mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Land. Since May 10, 2021, recurring attacks by gold miners on various Yanomami villages in the region of River Uraricoera have sown terror and constant threats, drastically reducing the freedom of the communities to conduct their daily activities such as fishing, hunting or tending their fields. The last Yanomami victim was a 25-year-old man who was run over on a clandestine airstrip for gold mining in the Homoxi region by a miner’s aircraft. In October 2021, the Hutukara Yanomami Association reported yet another tragedy: two children, aged 5 and 7, from the Makuxi Yano community, were swallowed by a gold mining dredge and thrown back dead into River Uraricoera.[14]

The Munduruku people have also been facing the consequences of the encroachment of mining in their territories. According to data from the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA), during the Jair Bolsonaro administration mining devastated more than 2,200 hectares of the Munduruku Indigenous Land in the municipality of Jacareacanga (Pará)[15]. On March 25, 2021, the base of the Munduruku Women’s Association Wakoburum suffered a violent attack by miners who operate illegally within Munduruku territories. The building – where women strengthen their support networks to ensure protection of their livelihoods and sell handicrafts – was destroyed and set on fire by the criminals.

A little over two months later, on May 26, the house and family of Maria Leusa Munduruku, coordinator of the association, were victimized by new attacks, when armed gold miners shot and then set fire to the leader’s house, fomenting moments of true despair. Other leaders who took a stance against mining have also been intimidated and threatened.

Illegal mining is responsible for alarming rates of environmental destruction, social disruption, and violence against indigenous peoples. At the same time, illegal mining is also one of the greatest human exploitation work environments. According to a survey by the Mining Observatory, more than 300 workers have been rescued in Brazilian mines in conditions similar to slavery in 31 operations since 2008, mainly in the states of Pará, Amazonas, Amapa, Rondônia, Mato Grosso and Bahia.

Faced with this devastating scenario, it remains on the hands of the indigenous communities and organizations, the entire indigenous movement and its allies, but also of society as a whole, to intensify their efforts to protect life and guarantee hard-won rights, so that Brazil can ensure the goal for coexistence and a healthy environment, and indigenous peoples can continue building their life projects and “Well Living”, with freedom and courage.

Notes

ISA. “Gold mining at Munduruku Indigenous Land increases by 363% in 2 years, according to ISA survey” (in Portuguese). Last accessed on August 1, 2021.

Luis Ventura Fernández is a missionary at Cimi Regional Norte I.