Deforestation as an instrument of land grabbing: enclosures along the expansion of the agricultural frontier in Brazil

By Diana Aguiar and Mauricio Torres

From the infamous “Day of Fire” in August 2019 – when rural producers orchestrated a joint attack with fire against the forest – to the fires covering the sky of São Paulo with thick clouds of smoke in September 2020, the last two years have been marred by environmental devastation in Brazil’s Amazon, Pantanal, and Cerrado regions. While images of scorched wildlife and vast landscapes in flames do and should evoke our indignation, the conflictive and criminal dynamics behind the forest fires, as well as the fact that fire is constantly used as a tool for territorial control, are often neglected.

Fire is an element of nature that has been wisely managed by indigenous peoples and traditional communities for centuries. Its traditional uses are carefully implemented, on small portions of land and in the appropriate season, as part of the long-term management of agroforestry landscapes[1]. Criticisms of those uses[2] are not only unfounded and disrespectful but are also a smokescreen to divert attention from the origins of most forest fires.

Contrary to traditional practices, the use of fire in agribusiness-sponsored land grabbing (grilagem) occurs on large expanses of land and is directly or indirectly associated with deforestation to expand the agricultural frontier. In these cases, fire is used to consolidate illegal land takeovers, both to cover up invasions of public land and environmental crimes (illegal deforestation)[3], and to conclude the deforestation process, providing an immediate appearance of land in agricultural use and preparing the area to be used as pastureland or, in some regions, for monoculture plantations. Fire – when associated with deforestation – is also often used as a weapon against indigenous peoples and quilombola, traditional and peasant-based communities.[4]

Notes

See more in this Dossier: Knowledge from afar: traditional fire use in the Cerrado and Amazon.

In a speech at the opening of the UN General Assembly on September 22, 2020, President Jair Bolsonaro stated that “fires happen in practically the same places, in the eastern outskirts of the forest, where ‘caboclos’ and ‘indians’ burn their fields as a survival strategy, in areas that have already been deforested,” implying that indigenous peoples and traditional communities are to blame for forest fires.

See more in this Dossier: Dangerous Liaisons: International pension funds, wildfires and land grabbing in Matopiba.

See in this Dossier, in the section “Land conflicts in the wake of fire” reports on several territorial conflicts that systematize this dynamic.

Deforestation expands along with the agricultural frontier

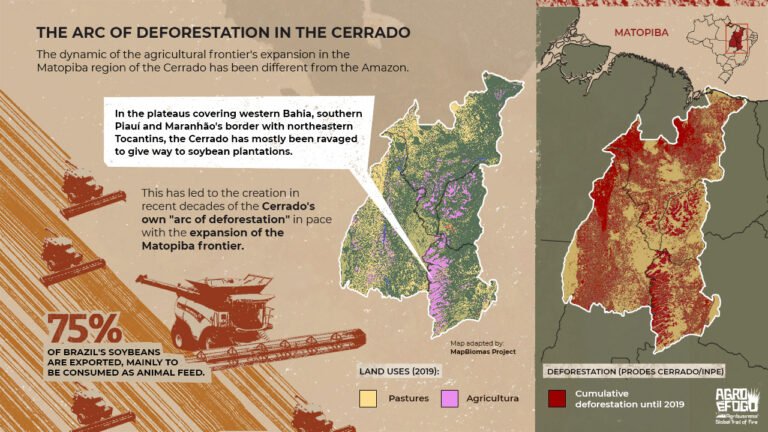

The map of accumulated deforestation in the Amazon, Cerrado and Pantanal provides clues for an understanding of these processes. As the frontier of Brazil’s main agricultural commodities – beef and soybeans – advanced over the years from the Center-South towards Central Brazil and from there into the Matopiba[5] and Amazon regions, so did deforestation to clear pastures and fields for monocultures. The aggregate national and regional data on evolving major land-use patterns corroborate and refine our understanding of this correlation.

From 1985 to 2019, a period that coincides with the emergence and consolidation of the agribusiness economy,[6] 90% of deforestation in Brazil was done to open land for pastures and monocrops and 10% for other purposes[7]. Aggregate numbers, however, do not fully explain the relationship between expanding agricultural frontiers and deforestation. Data on changing land-use patterns in specific regions helps us refine our interpretation of the role of soybeans and the relations between livestock and soy plantations in these processes.

From 2000 to 2014, more than 80% of soybean expansion in the Cerrado of the Center-West replaced pastures and other crops[8], pushing new pasture areas further into the Amazon forest (especially in northern Mato Grosso and southern Pará)[9]. Highways connecting Central Brazil to the Amazon were the main arteries for this movement. The Belém-Brasília (BR-153) and Cuiabá-Porto Velho (BR-364) highways, both built by the Juscelino Kubistchek (JK) government (1956-61), are considered milestones in the formation, starting in the 1960s, of the so-called “arc of deforestation”[10] – a region consisting of 256 municipalities where forest destruction has historically been concentrated and where the Ministry of the Environment used to focus its public policies to combat deforestation, when it still had such policies.

Notes

“Matopiba” is the Cerrado region located in the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia.

For a deeper analysis of the periodization proposed by the economist Guilherme Delgado, from which we draw inspiration, see: Guilherme Delgado. Do capital financeiro na agricultura à economia do agronegócio. Porto Alegre: Ed. UFRGS, 2012.

See also in this Dossier: Agribusiness and the Brazilian State: turning deforestation into profits

See Collection 5.0 of Mapbiomas (2020).

Arnaldo Carneiro Filho and Karine Costa. A expansão da soja no Cerrado: Caminhos para a ocupação territorial, uso do solo e produção sustentável. São Paulo: INPUT e Agroicone, 2016.

Brazil–Federal Government. Plano Nacional sobre Mudança do Clima – PNMC. Brasília: Comitê Interministerial sobre Mudança do Clima, 2008, p. 59 and 60.

One of the less discussed outcomes of this process is the reduction in the planted area of food crops important to family farming and to Brazilian families, such as rice, beans, and cassava, giving rise to supply shortages. For more see: Sílvio Porto and Diana Aguiar. “Os caminhos da insegurança alimentar” in: Dossiê Crítico da Logística da Soja: Em defesa de alternativas à cadeia monocultural. Rio de Janeiro: FASE, 2021.

Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). Nova geografia do arco do desmatamento. December 2019.

The arc extends from western Maranhão and Tocantins, south and southwestern Pará, through northern Mato Grosso, Rondônia and Acre, in a swath along the Cerrado-Amazon transition zone. Since deforestation and land grabbing go hand in hand, the Cerrado-Amazon transition is also the region with the highest intensity of rural conflicts in the country[11]. Besides this more consolidated arc of deforestation, the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the Amazon also benefited from the same BR-364 and other highways opened during the Military Regime (1964-85) that advance into the heart of the forest, such as the BR-319 (Manaus-Porto Velho) – with a pavement project now underway in Jair Bolsonaro’s infrastructure program[12] – and the BR-163 (Cuiabá-Santarém) – which, not by chance, was the main stage for the Day of Fire – giving rise to “new arrows of deforestation”[13].

During the same period, the dynamics of the agricultural frontier’s expansion into the Matopiba region of the Cerrado were different. There, in the plateaus covering western Bahia, southern Piauí and Maranhão, on the border with northeastern Tocantins, the Cerrado was cleared to make way for soybeans: more than 60% of this crop’s expansion in the region between 2000 and 2014 took place in areas where native vegetation gave way to soybean fields[14]. Thus, in recent decades, a new “arc of deforestation” has also emerged in the Cerrado, mostly over and around the Urucuia-Bambuí Aquifer System, and associated with the expansion of the frontier in Matopiba.

Notes

Analysis based on data from rural conflicts documented by the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT). See: Carlos Walter Porto-Gonçalves. Dos Cerrados e de suas riquezas: de saberes vernaculares e de conhecimento científico. Rio de Janeiro and Goiânia: FASE and CPT, 2019, p. 29.

See in this Dossier: Chronicle of a tragedy foretold on Highway BR-319.

ISA, 2019.

Carneiro Filho e Costa, 2016

Those numbers also debunk a common myth that soybeans are not an important driver of deforestation in Brazil. On the contrary, soybeans cultivated in the country – 75% of which are exported[15] – are indeed a major direct (in the Matopiba savannahs) or indirect (pushing agricultural fields and livestock pastures into the Amazon rainforest) driver of deforestation, depending on the region analyzed.

Notes

Diana Aguiar. “As rotas pandêmicas da cadeia global do complexo soja-carne”. In: Dossiê Crítico da Logística da Soja: Em defesa de alternativas à cadeia monocultural. Rio de Janeiro: FASE, 2021.

Expansion of agricultural frontier depends on the private appropriation of land

Despite slick advertising campaigns in a major TV channel in Brazil about agribusiness (“AGRO”) being “tech”, as well as the actual adoption in the last half century of commodity production dependent on technological packages (genetically modified seeds, chemical fertilizers, pesticides and machinery), the expansion of this production was mainly due to the expansion of pasture lands (especially in the Amazon) and monoculture areas (especially in the Cerrado)[16]. Productivity gains and productive intensification were significant mainly in older agricultural frontier zones in the Center-South, but had less relative impact on the aggregate increase in production volume, which mainly benefited from the expansion of the frontier. In this sense, these activities reinforce aspects typical of the colonial plantation economy that has plagued Brazil for 500 years: since they are extremely land and water intensive, they promote land concentration and environmental injustice[17].

The private appropriation of large expanses of land is, therefore, a precondition for agribusiness to be able to spread its livestock and crop monocultures. One manifestation of this is the gradual transformation of land tenure from a predominance of informal land possession to the establishment of property regimes in certain regions, in step with the advance of the agricultural frontier[18]. This, however, does not mean that the property deeds are proof that such rural lands have been incorporated into someone’s private holdings legally, considering that the origin of all Brazilian land is public[19].

On the contrary, it is rare to find deeds to large rural properties in MATOPIBA (the main frontier of the Cerrado today) or in the Legal Amazon (which also encompasses some Cerrado and Pantanal areas) with valid chains of succession that document the moment when public property was detached and legally transferred to private property. In most cases, these properties have at some point undergone fraudulent procedures to give the property records the appearance of legality[20]. Besides systematic checking of specific deeds that unquestionably confirms this, another structural proof is the fact that, since 1946, there has been a limit of 10,000 hectares on the transfer of public lands to a single private person, rendering the occurrence of large estates of tens and even hundreds of thousands of hectares in MATOPIBA and the Legal Amazon unjustifiable from a legal standpoint[21].

The massive illegal privatizations of public lands share some common legal forms, such as forgery of the original deed for the private property or of its surface area[22]. It is common to find documents that are not even valid proof of property (such as certificates or titles of possession or certificates of claims filed for the alienation of the area) blatantly presented as original deeds to register the sale of the property[23]. More recent innovations include the use of the Rural Environmental Registry (Cadastro Ambiental Rural/CAR, an environmental management instrument created by the 2012 Forest Code), as if it were proof of ownership, although this is expressly prohibited by law[24].

In the CAR, the alleged owner or holder declares the size of the area, the location of the mandatory legal reserve, etc., in order to prove the property’s environmental compliance. However, because the CAR is self-declaratory and the statements are rarely examined and validated by authorities, the registry has facilitated land grabbing, especially a new modality often referred to as “green grabbing” (grilagem verde)[25]. It involves the declaration by farmers and rural entrepreneurs or enterprises that their property includes what are in fact public lands and traditional territories, as a means to perpetrate notary fraud.

Especially in the Matopiba region of the Cerrado, “green grabbing” through the CAR has enabled the expansion of illegal land appropriation and deforestation. It has become common that, after taking over areas of common use from traditional communities (for instance, in the “gerais”, traditional name for the “plateaus” of western Bahia) over decades of agricultural frontier’s expansion, the same rural enterprises declare their legal reserve areas over the remaining community areas (in the valleys, to use the same example) – areas where the savannah is still standing precisely because of their traditional occupation and management. This process is aggravated by the fact that the Forest Code allows areas that are not contiguous to the “properties” being registered to be declared as their legal reserve[26]. Thus, under the pretense of fulfilling the obligation to preserve their legal reserve elsewhere, these enterprises deforest the parcels they had previously kept as legal reserves in the area that they had grabbed and held for the longest time.

These processes involve everything from the crudest to the most sophisticated procedures. Moreover, they are not performed in an arbitrary or isolated manner by operators who are unaware of the dimensions of agribusiness. On the contrary, to operate the various modalities of large-scale land grabs, there is an ongoing involvement of a chain of relationships, often involving a combination of players ranging:

“from gunslingers to notary publics, local politicians, police officers, lawyers, magistrates, prosecutors, officials of land and environmental agencies, legislators, public authorities, etc. At the top of this chain are the transnational agribusiness traders, banks, and international investment funds, which acquire, trade, and mortgage the illegally appropriated lands.”[27]

It is above all at the tip of the chain most dominated by local and regional players that deforestation is systematically used as a tool for a very common form of land grabbing (called grilagem), helping to ensure that, once public land has been illegally appropriated, it can be made to appear as if it is legally registered and can then enter the land market.

Notes

See in this Dossier: Agribusiness and the Brazilian State: turning deforestation into profits

See: Porto-Gonçalves, 2019, p. 27.

Joice Bonfim, Debora Assumpção, Juliana Borges, Mauricio Correia and Silvia Helena Coelho. Legalizando o ilegal: legislação fundiária e ambiental e a expansão da fronteira agrícola no Matopiba. Salvador: AATR, 2020.

The 1850 Land Law defined the so-called public origin of Brazilian land and the need to comply with specific requirements for the legal transfer of land from public to private ownership. See more here: Bonfim et al, 2020.

Bonfim et al, 2020.

Mauricio Torres; Juan Doblas; Daniela Fernandes Alarcon. “Dono é quem Desmata”: conexões entre grilagem e desmatamento no sudoeste paraense. Pará: Instituto Agronômico da Amazônia, 2017.

Bonfim et al, 2020.

Torres et al, 2017.

For more details, see: Bonfim et al, 2020, p. 44-46.

For a detailed description of traditional and novel forms of land fraud schemes (grilagem), see: Bonfim et al, 2020; Torres et al, 2017.

Art. 29, § 2 of Federal Law No. 12,651/2012.

Bonfim et al, 2020.

Bonfim et al, 2020.

Bonfim et al, 2020, p. 8.

Deforestation as an instrument of land grabbing

For decades, Brazilian agrarian social movements and scholars have struggled against and analyzed a specific strategy of land grabbing that involve, as a key step, diverse types of fraud in property deeds, taking advantage of Brazil’s so called “land-tenure chaos” (caos fundiário). The name “grilagem” (in a literal translation, “cricketing”) has been widely used in reference to an old process of storing the fake documents in a drawer with crickets (grilos) so that the insect’s waste over a period of time would give an appearance of yellow aged papers, making the fraud look more authentic. Although no longer a practice amongst grileiros (the land grabbers adopting such a strategy), the term has survived the test of time to characterize this type of land grabbing.

Both those old and now the contemporary forms of grilagem consist, roughly speaking, of two complementary phases: land grabbing “on the ground” (the illegal invasion and control of public lands) and achieving the appearance of legality “on paper” (the bureaucratic part). The clearing of forest and native vegetation on the land being appropriated is the main instrument towards consolidating the takeover, as well as a basis to the subsequent process of “laundering” the land at the notary public, where what is actually an environmental crime (illegal deforestation) can absurdly constitute proof of productive occupation. The easier it seems to give an appearance of legality to grabbed land (grilar), the greater the chances are that the land grabber (grileiro) will invest heavily in the first step: clearing vast areas and possibly threatening and expelling their previous occupants. The maxim “The owner is the one who clears the forest,” voiced by a land grabber in western Pará, expresses the harsh reality that whoever deforests an area will, in fact, always be recognized as its owner in the local logic of the frontier, and will often consolidate the fraud by receiving a deed for the stolen land[28]:

Even though the state may issue millionaire fines (very rarely paid) and, even more rarely, order someone’s arrest, the repossession of illegally appropriated public lands never happens. The person who cleared the forest is recognized as the land’s owner – he is even commonly rewarded by recent public policies with broad loopholes to legitimize land grabbing[29].

Ever since the Land Law of 1850, whose norms still have an impact on today’s land regime, there has been a succession of amnesties for environmental crimes and legalizations of illegal take overs of public land. Even under the 1988 Constitution – with its important landmarks towards recognizing the social function of property, the priority of Agrarian Reform and the territorial rights of indigenous peoples and quilombola communities – a gradual process of legislative flexibilization and continuous threats to enshrined rights has been orchestrated by a parliament dominated by rural landowners’ lobbies[30]. The land grabbers/deforesters’ certainty of impunity, and their confidence in future amnesties and legalization, all make the theft of public lands a routine practice and fuel even more deforestation, which goes hand in hand with land grabbing.

Perhaps the most striking evidence of this linkage comes from satellite images of deforestation in neighboring areas with different land-tenure categories. They reveal how deforestation takes place mostly in undesignated public lands, while on designated public lands – such as conservation units and indigenous lands – it is contained. This correlation holds even in the many “paper parks”, meaning conservation units approved by federal or state authorities, but with no relevant or concrete “on the ground” management. In other words, even with no practical, local obstacles to deforestation, such as demarcation or enforcement activity, there is mostly no deforestation in designated areas. It is enough for the decree for a new protected area to be signed for deforestation to decline and, especially in the case of the Amazon forest, for illegal logging to increase.

Notes

Torres et al, 2017.

Torres et al, 2017, p. 1

Obviously, the drop in deforestation in newly decreed protected areas does not vouch for the deforesters’ good intentions, but rather comes in response to the new land tenure status, which is no longer amenable to gaining a legal private appearance (key in grilagem-type land grabbing). The dynamics show a correlation between forest suppression and the plundering of public lands: the land grabbers know that an already designated public land cannot be withdrawn from the public domain and changed into private property. Since deforestation is expensive – despite the systematic use of slave labor – there is no justification for a land grabber to clear an area that he will not be able to appropriate and then dress up as legal. On the other hand, all it takes is for a public debate to begin about reducing the limits or withdrawing a conservation unit from public use – as in the case of the Jamanxim National Forest – and deforestation will skyrocket inside the area,[31] triggered by the land grabbers’ perception of a future opportunity for “legalizing” the private appropriation of the land through fraud. This is testament to the deep connection between environmental and land tenure issues in Brazil.

Notes

Mauricio Torres; Sue BRANFORD. Amazônia ou parque dos dinossauros. The Intercept, April 4, 2017.

TORRES, Mauricio; BRANFORD, Sue. Governo está prestes a aprovar projetos a favor de grilagem e outros crimes ambientais. The Intercept, June 13, 2017.

Marcos Furtado. Pará tem 8 das 10 unidades de conservação mais desmatadas da Amazônia. O Eco, Oct. 18, 2020.

The difference between deforestation and environmental/forest degradation

The term “deforestation” refers to the complete removal of forest cover or native vegetation, also called “clear cutting”. It is only detected on satellite images when it occurs in a continuous area larger than 6.35 hectares. It is essential for the land to be used for monoculture, which entails the substitution of the area’s biodiversity by planting one or a few species, or for large-scale cattle raising, by suppressing the forest or even natural pastureland to be planted with industrial pastures.

Knowing the limits of satellite monitoring, land grabbers may remove the lower stratum of the forest to cover up ongoing deforestation or even carry out rounds of deforestation in different parts of an area each year, to evade detection by satellites for a longer period of time[32]. In such cases, “forest or environmental degradation” of an area may occur before the deforestation is consolidated.

Forest degradation can also arise from situations where clear cutting is not the ultimate goal, such as selective logging for illegal lumber trade (usually on designated public lands) in the Amazon. In these cases, logging roads are opened, commercially valuable trees are cut, and small operational yards are cleared (called esplanades). Even though the forest is greatly degraded in these processes, it is not possible for the deforestation monitoring system to detect the change in land cover[33]. Furthermore, even though the situation is not strictly speaking deforestation and is not necessarily associated with grilagem, it may mean other forms of land grabbing and is no less dramatic: it usually involves the systematic use of slave-like labor and is often carried out by a lumber mafia that terrorizes communities living inside conservation units, agrarian reform settlements, and indigenous lands where the lumber is looted[34].

Notes

This dynamic has been observed in certain cases analyzed in the Cerrado region, in an ongoing research project.

Centro de Defesa da Vida e dos Direitos Humanos Carmen Bascarán – CDVDH/CB and Comissão Pastoral da Terra – CPT. Por debaixo da floresta: Amazônia paraense saqueada com trabalho escravo. São Paulo: Urutu-Branco, 2017.

Torres et al, 2017.

See in this Dossier: Slave labor, expropriation and environmental degradation: a visceral connection.

See in this Dossier, several conflicts described in the section: Land conflicts in the wake of fire.

In the process of grilagem-type land grabbing, deforestation serves a number of functions. One of the most obvious is to push up land prices. In western Pará, in 2017, a piece of deforested land could fetch up to 20 times the price of an equivalent area covered by forest. Land buyers in the region stated that they preferred to pay more for land that was already cleared, even though some were willing to buy areas with forest cover. In some cases, deforestation actually made the land marketable[35]. Furthermore, the very announcement of public infrastructure works intensifies this type of process: when the paving of the BR-163 highway was announced, deforestation rates in the region spiked and the market for illegally appropriated land boomed[36], highlighting the relationship between land grabbing, deforestation and real estate speculation.

Another function of deforestation in the grilagem-type land grabbing cycle is to prove de facto occupation as a ticket into permissive public policies that also help legalize land grabbing. The Legal Land Program, created by Law 11,952/2009 and altered by Law 13,465/2017, for example, accepts as proof for dating occupation the deforestation records in satellite images. In western Pará, things can get so outlandish that a person illegally clears a forest area and then calls the environmental police – the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) – to later file the Notice of Infraction issued by the federal authority as proof of productive occupation[37].

Inherent in the nexus between clear-cut land and productive tenure is a long-standing premise underlying the social construction of the Brazilian state since the colonial plantation economy and trailblazing Bandeirantes times, later to be consolidated in the conservative modernization fostered by the Military Regime, and whose most perverse face has re-emerged in Bolsonaro’s anti-environmentalism. It is the idea that land must be “developed”, i.e., incorporated into production and market circuits, equating agricultural frontier openers with an image of pioneering entrepreneurs and trailblazers who confront “wild nature” to bring progress to remote regions. Such imagery portrays the forest and other types of native vegetation as obstacles; and, above all, indigenous peoples, quilombola communities, and other traditional and peasant-based communities are viewed as backward remnants of a past that is doomed to extermination.

Therefore, another no less important “function” of the cycle of deforestation and fire in the process of illegal appropriation of public lands is their systematic use as weapons against peoples and communities, to threaten and displace them from their lands. This process promotes territorial fragmentation and restrictions, and eventually keeps communities from reproducing their own ways of life. The invasion of traditional territories often begins precisely in the communities’ common-use areas, and soon overtakes their living quarters and home gardens. The section “Land conflicts in the wake of fire” in this Dossier contains various recent examples of this strategy used by deforesters in the Amazon, Cerrado, and Pantanal, and of the dramatic consequences for communities.

Notes

Torres et al, 2017.

Torres et al, 2017.

See in this Dossier: Chronicle of a tragedy foretold on Highway BR-319.

Mauricio Torres. “Fronteira, um eco sem fim”. In: Maurício Torres (org.). Amazônia revelada: os descaminhos ao longo da BR-163. Brasília: CNPQ, 2005.

Agrarian reform for ecology and rights

Our analysis up to this point shows that the dynamics of deforestation are never fully portrayed by satellite images of suppressed native vegetation. While these may identify important components of environmental issues in Brazil, without an analysis of agrarian and land tenure issues, we still miss much of what is really going on. Deforestation and forest fires devastate not only the vegetation cover, but also the biodiversity and ways of life in traditional territories.

At the core of the cycle of deforestation, fires, and land grabbing lies the erosion of biodiversity and of traditional knowledge associated with it. It is peoples and communities who defend the forests and other native vegetation cover, often with their own bodies. The areas under their possession are the most protected and richest in biodiversity in the Amazon, Cerrado, and Pantanal. Guaranteeing their tenure, through the demarcation and regularization of indigenous lands, quilombola territories, extractive reserves (RESEX), and other forms of land tenure regularization for traditionally occupied territories, as well as agrarian reform settlements, is therefore not only a matter of rights, but also an essential political strategy to curb deforestation – along with the erosion of biodiversity and associated knowledge. By opening the passage to land grabbers, Brazil trades its greatest wealth for the profit of a rural elite whose production supplies the transnational chains of a limited range of agrifood commodities.

Major pieces of legislation over the years have reiterated the priority of allocating public lands for agrarian reform and environmental protection. In addition, the legitimacy of possession of public lands depends on compliance with certain conditions: specific to peasant occupations, of less than 100 hectares, that meet specific, long-standing legal requirements, unlike land grabbing on public lands. Decree-Law 9,769, of 1946 (as amended by the Land Statute, in 1964), explicitly proscribes any possession on federal lands, except for those consistent with an occupation that, here, we shall call peasant occupation:

Art. 71. The occupant of Union [i.e. federal] property without its assent may be summarily evicted and shall lose, without right to any compensation, everything he has incorporated into the soil, being further subject to the provisions of arts. 513, 515 and 517, of the Civil Code.

Sole Paragraph. Exception is made from this provision for good faith occupants, with effective cultivation and habitual dwelling, with rights assured by this decree-law.

For such a holding or possession to qualify for legalization, the holder must be able to demonstrate their own agrarian possession comprehending, far beyond animus domini, the combination of effective cultivation and habitual dwelling. In addition, it is essential that “this combination be grounded on the absolutely indispensable basis of direct and personal use, by the possessor and his family members, as expressly required by the Land Statute”.[38]

From a legal standpoint, land possession is, therefore, a social reproduction strategy associated with peasant farming. It is antithetical to the illegal appropriation of public lands (land seizure) consolidated through land grabbing mechanisms associated with the primitive accumulation of capital. Despite the explicit legal differentiation, private land-grabbing groups have frequently called themselves posseiros (a term connected to the legal possession of public land by peasants), in the hope of convincing authorities that their holdings are legitimate and legal[39]. Despite not qualifying at all as posseiros (squatters), they frequently resort to the procedure of dividing vast areas of stolen land into smaller plots registered in the names of dummies (laranjas) or of several members of the same family, to circumvent the legal limitations to the regularization of land tenure.

Land grabbers (grileiros) posing as squatters (posseiros) is an old and recurrent scheme. The strategy is strikingly clear – and even embarrassing – in a statement by the current Special Secretary for Land Issues of the Ministry of Agriculture, Luiz Antônio Nabhan Garcia, who is also the leader of the most reactionary agribusiness coalition in the country, when he released the Provisional Measure that the Bolsonaro government had drafted in September 2019: “After this government, the terms occupant, squatter and land-grabber will no longer exist.”[40]

Several so-called “land regularization” programs have in practice become programs to legitimize land grabbing with the systematic theft of public lands and the expropriation of traditional communities. The most prominent of such programs, the Legal Land Program, put together between 2009 and 2017, rests on a legal framework to facilitate the deeding of illegally appropriated public lands. By and large, the program does respond to a real need for “land regularization” and, under this generic designation, provides flexibility to the rules of alienation of federal lands into the hands of private parties. A recent study by Torres, Cunha and Guerreiro systematizes the flexibilities introduced by the legislation that underlies the Program and shows how they have gradually established legal criteria for the alienation of federal public lands through new preferential conditions for groups previously legally recognized as land invaders or grabbers (grileiros).[41]

The World Bank and several market-oriented environmental organizations see the granting of deeds to public lands as the solution to a “legal insecurity” that supposedly limits investments and the formation of a real estate market. Their liberal rationale assumes that private property can solve everything. They thus exclude anyone who approaches land as commons and a territory, and for whom recognition is the main way to have rights respected.[42]

Understanding how the cycle of deforestation, forest fires, and land grabbing enables a strategy for the private appropriation of land leaves us no other path than to defend agrarian reform in its broadest sense, including the recognition of peoples’ and communities’ territorial rights, as both an ethical imperative and an ecological necessity.

Notes

Ismael Lima Falcão. Direito agrário brasileiro: doutrina, jurisprudência, prática. Bauru: Edipro, 1995. p. 81 [italics in the original].

Torres et al, 2017.

Apud Paulo Silva Pinto. Regularização de terras deverá ter medida provisória. Poder 360, Sept. 25, 2019.

Mauricio Torres; Cândido Neto da Cunha; Natalia Ribas Guerreiro. “Ilegalidade em moto contínuo: o aporte legal para a destinação de terras públicas e a grilagem na Amazônia”. In: Ariovaldo Umbelino Oliveira. (org.). A grilagem de terras na formação territorial brasileira. São Paulo: FFLCH/USP, 2020.

Mauricio Torres, 2018.

Diana Aguiar is a professor and researcher at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) and an advisor to the National Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado.

Mauricio Torres is a professor at the Amazon Family Farming Institute (Ineaf) at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

We thank Eduardo Barcelos of the Bahia Federal Institute/Valença Campus for organizing the cartographic bases used to compile the various infomaps used in this article.