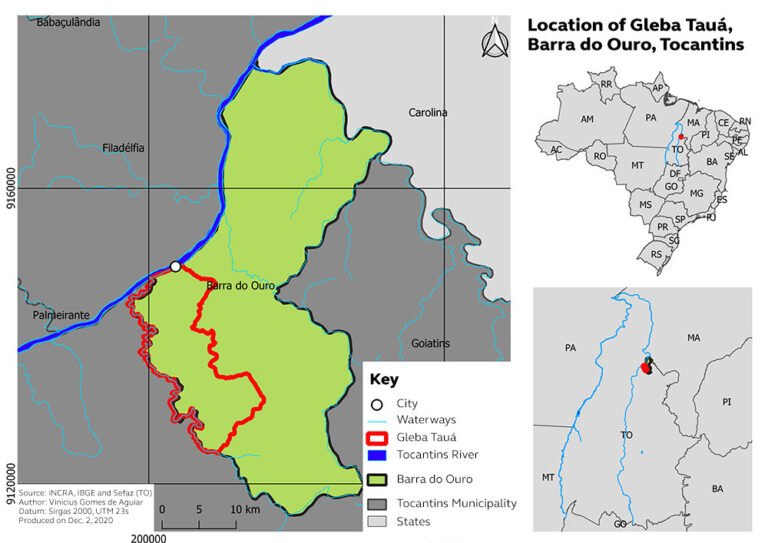

Tauá is a large traditional territory in the state of Tocantins, occupied for over 100 years by peasant families who migrated to the region from the states of Maranhão and Piauí. The territory is located between the Tocantins, Ouro, and Tauá rivers, in the municipality of Barra do Ouro, in the northeast region of the state, about 420 km from the capital Palmas. The microregion comprising the municipalities of Barra do Ouro, Goiatins and Campos Lindos is predominantly made up of Cerrado vegetation, which has been devastated to make way for soybean, corn and eucalyptus monocultures over the past 30 years – along with relatively older large cattle pasture areas.

This peasant land shared as a commons began to undergo intense transformations with the regularization of land ownership imposed near the end of the military dictatorship (1964-85). Since it is within 100 km of Federal Highway BR 153, it is considered to be federal land. As such, in 1984, the Araguaia-Tocantins Executive Land Group (GETAT) reclaimed the area covering 17,735 hectares. The land was reclaimed without the consent of most of the people who lived and worked there. GETAT then titled only 5,779 hectares as individual lots to a minority of the peasants, leaving 11,956 hectares of federal land traditionally occupied by many other peasant families who were not granted titles.

The many peasant families who did not have their lands titled were left vulnerable to an ambitious land grabbing plan launched in 1992 by Emilio Binotto and his relatives from the state of Santa Catarina, in Southern Brazil. Even for peasant families who did have their land regularized, however, their titles were no guarantee of being able to remain on the land. On the contrary, they were used as leverage for the land grabbers to pressure each legal owner individually to sell their farms. This meant no rest for the families, who recall that when the Binottos appeared in the region, they brought along machinery to work the land, and, as soon as they managed to expel the first resident, started to clear the trees to plant soybeans.

From then on, residents with titles began to be pressured, at times with violence, by burning down their homes and killing their livestock. Frightened, many families sold their lands to the grileiro (land grabber), who, in possession of some titles, surrounded other public areas still worked by their long-time occupants. The families’ distress was caused not only by physical, material, and moral violence, but mainly by cultural violence against their ways of life. After the land grabbers arrived, even the communities’ sacred spaces were destroyed or violently disrupted by soybean plantations, such as their eight cemeteries.

In 2004, the Binotto family petitioned the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra) to regularize seven areas, each in the name of a different family member. Their tactic for land grabbing was to subdivide the 11,000 hectares of land that GETAT had refused to grant to the peasant families. The first request was rejected, but in 2010, soon after the creation of the Legal Land Program (Programa Terra Legal) and with new land tenure regularization laws in place, the Binotto family once again filed for regularization of the land they had illegally taken over. This time, they split the 11,000 hectares into 14 parcels for people connected to the family, expanding the consortium of land grabbers.

In 2007, the peasant families lodged their first accusation of land grabbing, deforestation, and threats by the Binotto families at the Office of the National Agrarian Ombudsman (OAN). In 2008, after an official inspection of the Tauá site, Incra initiated an administrative procedure to regularize the land of the traditional squatters and establish settlements for them. But it was only in 2015, after much pressure from the families and the Araguaia-Tocantins Pastoral Land Commission (CPT), with denunciations filed before the Federal Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), the National and Regional Agrarian Ombudsman’s Office, the National Superintendent of Land Regularization in the Legal Amazon (SRFA-9) – connected to the Legal Land Program – and the Office of the Solicitor General of the Union (AGU), that all the land regularization applications filed by the land grabbers were rejected. All 14 areas they claimed illegally were withdrawn and allocated to regularize the land tenure of the traditional squatters and to create a settlement for the occupying families.

However, in 2016, after all the lawsuits and mobilizations that had proven the land grabbing, the judge of the District of Goiatins issued an eviction injunction against the squatters’ and occupants’ families. In 2019, a Federal Court Decision ordered Incra to proceed with the land regularization process of 4 squatter families, but in response to a different lawsuit filed by the land grabber against the occupying families, the Court recognized the land grabbers’ right of possession over one of the 14 areas, one of the occupying families’ settlement areas. In practical terms, there was some progress in the administrative and judicial lawsuits in favor of the communities, but the rulings have done little to ensure the safety of the families or to prevent environmental destruction in Tauá. Today, more than 100 families live in Tauá, including 20 peasant squatter families still seeking land title regularization; 60 squatter families seeking agrarian reform; and more than 30 traditional peasant families whose farms have been granted land titles.

Emilio Binotto’s land grabbing in the Tauá region has spread fear, displaced residents and accelerated the destruction of the Cerrado to plant soybeans, corn and cattle pastures. Ever since Binotto’s invasion, families in Tauá have experienced systematic attempts at expulsion. Sometimes it is through violence, with gun shots against the residents’ homes and animals; at other times it is the poisoning of the streams that supply the homes with water; and in other locations it is deforestation followed by fires that destroy homes, fields, work equipment, and plateaus.[1]

Notes

“Casa é destruída por fogo em conflitos na Gleba Tauá”. G1.; Webseries (R)Existências no Cerrado: Comunidade Tauá – Tocantins. CESE, 07/13/2020.

Before, I used to walk through these lands and know exactly where every waterhole was, every path to the homes of friendly families. Today, with this open space, I don’t recognize anything anymore, and I can no longer find my way around”, exclaims Dona Raimunda, one of the territory’s leaders.

The following map shows the Gleba Tauá’s territorial boundaries, identifying large areas invaded by agriculture and cattle ranching and the encroachment of fires into remaining Cerrado areas, occupied by squatters and settler families.

Many complaints have been filed at environmental enforcement agencies, such as the Nature Institute of Tocantins (Naturatins), the Environmental Military Police, and the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama). In many cases, deforestation and fires wipe out the families’ production fields and homegardens (quintais), destroying their crops and income sources. According to Valdineiz Pereira, a community leader,

The purpose of deforestation and fires is to clear new areas as proof of possession of the land and to prepare new fields for soybean and corn plantations.

The peasant families continue to resist and fight for their land, and produce a variety of foods, despite being surrounded by soybean plantations and confined to small plots of land of less than 5 hectares. They continue to produce food on slash-and-burn fields and homegardens. In their fields, they grow cassava, corn, climbing beans, fava beans, pumpkins, rice, watermelon, and other foodstuffs.

From the homegardens around the home, the women feed and care for their families with vegetables, chickens, pigs, ducks, medicinal herbs, fruit, and cassava. They also generate income by selling free-range chickens and eggs, as well as fufu paste and tapioca starch. This is also where the cassava flour and rice mills are located. The family homegardens, about 2.5 hectares in size, produce the family’s basic food supply.

Valéria Pereira Santos coordinates the Pastoral Land Commission in the Cerrado region.

Vinícius Gomes de Aguiar is a professor and researcher at the Center for Research and Extension in Agroecological Knowledge and Practices – NEUZA/UFT/UFNT.

Dernival Venâncio Ramos Junior is professor and researcher at the Center for Research and Extension in Agroecological Knowledge and Practices – NEUZA/UFT/UFNT.

Pedro Antônio Ribeiro is an agent of the Araguaia Regional Pastoral Land Commission -Tocantins.

Valdineiz Pereira dos Santos is a Tauá community leader.